It struts around, it puffs its chest, but its numbers are plummeting. Governments are struggling to preserve enough habitat to save the bird.

When scientist Michael Schroeder was looking for a place to live in eastern Washington State, he chose to be within an hour and a half drive of seven species of grouse, the birds he has been studying for the last 22 years.

But when it came to North America’s largest grouse species, the greater sage-grouse, Schroeder, a scientist at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, had to bring in the birds himself.

Since 2008, his team has captured 279 sage-grouse in southern Oregon, where the population is more healthy, and has released them here in Lincoln County, Washington.

“Washington historically was a major part of the sage-grouse range. We had a lot of habitat here,” Schroeder says. “Because so many areas were converted for wheat, we no longer have the birds.”

WATCH: See how researchers from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife are helping the sage-grouse find a new home.

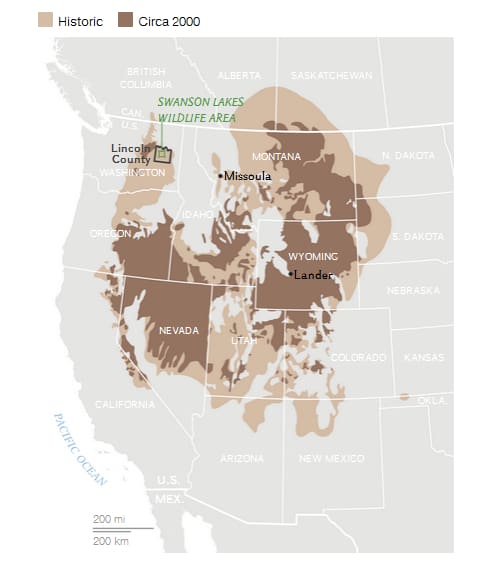

The greater sage-grouse is in trouble not just here but all over its range, which covers 165 million acres in 11 western states and two Canadian provinces. Once numbering in the millions, the bird has lost nearly half its sagebrush habitat to development—to farms and ranches, to oil and gas operations, to spreading cities, and lately to wind farms. Fire and invasive plants have also taken a toll.

Just between 2007 and 2013, the bird’s numbers plummeted by more than half, according to a study released in April by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The study found there are now fewer than 50,000 male sage-grouse engaged in the strutting, chest-puffing, tail-fanning courtship behavior that makes the two-foot-tall birds so charismatic.

Greater sage-grouse range

As things stand, says Edward Garton, professor emeritus of wildlife ecology at the University of Idaho and lead author of the Pew report, most of the 42 distinct populations of sage-grouse will likely go extinct within a hundred years. “In the long-term, it doesn’t look good at all except for three core populations” in Wyoming, northern Montana, and Idaho, Garton says.

Five years ago, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that the sage-grouse warranted protection under the federal Endangered Species Act—but it put off deciding whether actually to list the bird. Under a legal settlement with environmental groups, it’s required to decide by September 30. People all over the West are anxiously awaiting that decision. Since so many human activities affect sage-grouse, the economic impact of a listing could be large.

In Washington, where the sage-grouse population declined 80 percent between 1970 and 2014, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife listed the bird as threatened as long ago as 1998. Only 800 birds remain in four small isolated populations in eastern Washington. Those are the populations Schroeder is trying to boost with fresh recruits from Oregon.

Birds of the Open Range

Sage-grouse require vast tracts of undisturbed sagebrush to survive. It provides their only food in winter and shelter for their nests in spring. It surrounds their ancestral breeding grounds—the great clearings, called leks, to which they return in late winter.

Migrating seasonally between different parts of their range, the birds have been known to cover distances of up to 100 miles—if roads or fences don’t block their path. They tend to avoid all signs of human presence.

Since 2010, the threat of an endangered species listing has galvanized efforts to conserve the sagebrush steppe, bringing together federal and state agencies, private landowners and industry leaders, and conservation groups. Western governors have argued that it is up to the states to determine how to protect the birds. Wyoming, which has nearly 39 percent of the entire sage-grouse population, was the first to adopt a conservation plan that protects “core areas” of habitat. Other states have followed.

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the largest land manager in the West, is also devising regional plans, covering a total of 50 million acres, that will place some limits on human activities. Meanwhile the U.S. Department of Agriculture has invested nearly $425 million in a Sage-Grouse Initiative. The money has funded conservation easements covering 380,000 acres on some 1,100 ranches, along with other projects such as the removal of invasive conifers.

“The number of people that are thinking about sage-grouse today is just incredible compared to five years ago,” says Dave Naugle, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Montana in Missoula and the scientific advisor to the USDA initiative. The efforts on behalf of the sage-grouse, he adds, are helping preserve an ecosystem that supports 350 other species, including golden eagles, mule deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, and pygmy rabbits.

Will those efforts be enough? A few weeks ago, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that in one case they had been. The “Bi-State population,” a distinct segment of the sage-grouse population that straddles the California-Nevada border, doesn’t need protection under the Endangered Species Act, officials announced.

Environmentalists disagree—and worry that the decision may foreshadow the nation-wide one coming in September. “They did not address all the threats,” says Randi Spivak, public lands program director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Her group and others have also criticized the first conservation plan issued by the BLM, for the region of Lander, Wyoming; it allows new oil and gas leasing within core sage-grouse habitat, the critics say, and doesn’t protect winter habitat at all. “Extinction may be delayed but it won’t be avoided when you go with half measures,” Spivak says.

The ongoing population decline documented in the Pew study suggests the critics have a case. “A lot of money is being spent to try and do things that would improve habitat for sage-grouse—people are really trying to make an effort to reverse the continual decline,” says Edward Garton. “But unfortunately there is not much evidence that we are being successful.”

“In spite of all that great effort,” he says, the sage-grouse “is just as likely to go extinct as it was, if not more so.”

WATCH: See and hear sage-grouse on the lek as they search for a suitable mate.

A Lek Is A Happy Place

In eastern Washington, Michael Schroeder is not giving up. At 5 a.m. on a March morning, he leads a reporter and a videographer by flashlight to a large clearing in the sagebrush in Swanson Lakes Wildlife Area. Just a few years ago, Schroeder says, this lek was a very quiet place. Sage-grouse had been absent from the whole area since the 1980s.

But in the early 1990s, the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the BLM consolidated and acquired a total of 50,000 acres of habitat for sage-grouse. Since 2008, Schroeder has been reintroducing birds to this place—capturing them at night in Oregon with a spotlight and a net, then releasing them here the next day.

That’s only a first step. If the species is to endure in eastern Washington, the small, isolated populations that now exist will have to be connected somehow across a landscape fragmented by transmission lines, highways, urban developments, and wheat fields. “It is an uphill battle, we don’t know if it can be done,” admits Schroeder.

But right now he’s recharging his optimism. Just before dawn, the white spots slowly start to appear on the lek. We count 17 of them—17 male sage-grouse, their drab brown bodies practically invisible in the twilight, but their white, puffed-up chests standing out like light beams. They’re fanning their tails like peacocks too. All is quiet except for the bizarre, regular whistling and popping sounds the males emit. They will keep this up for hours.

Seventeen of them dance, but only a few will be chosen. Somewhere in the dark, female sage-grouse are watching and listening. Hiding in a blind that blends in with the sagebrush, so are we.

“That was a big highlight when we finally got to the point where we had birds displaying on the lek,” Schroeder says. “Now people can go out and watch the birds. That makes people very happy.”

This article was first published by National Geographic on 19 May 2015.

Leave a Reply