Ghost sharks, which sport retractable sex organs on their heads, have even more bizarre bodies than we thought.

A new study of the deep-sea dwellers reveals that some females have a built-in sperm storage bank that allows them to keep viable sperm for possibly years at a time.

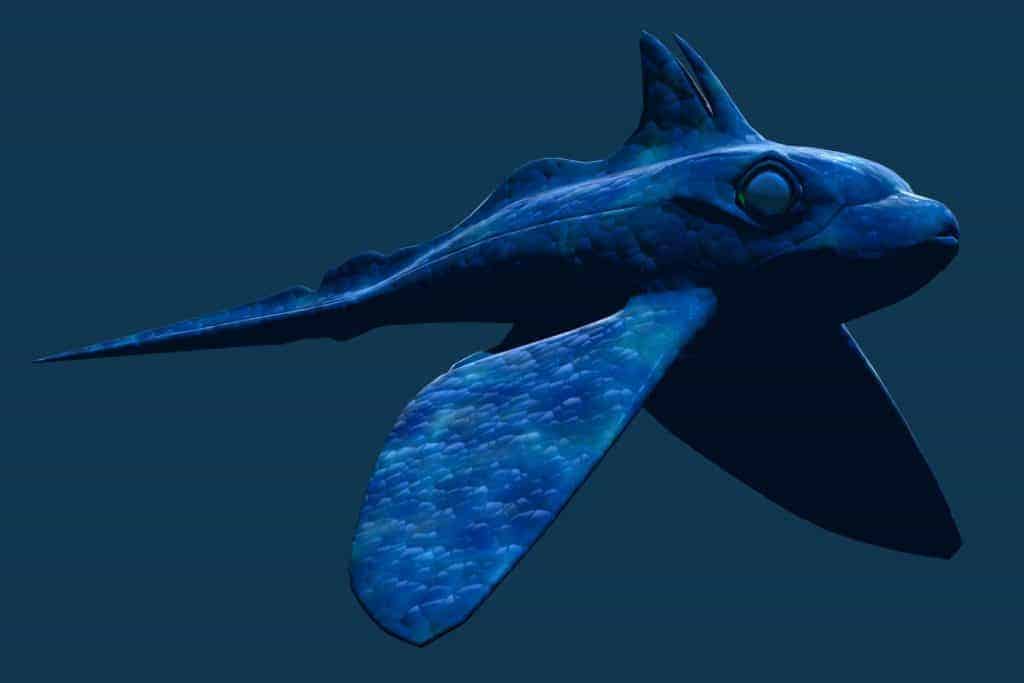

Also known as chimaera or ratfish, ghost sharks have long fins and vacant eyes that make even great whites seem friendly. Though ghost sharks are distantly related to sharks and rays, little is known about the rarely seen fish.

“They literally look like a fish put together by a committee,” says chimaera expert David A. Ebert, director of the Pacific Shark Research Center at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories in California.

For the study, scientists focused on two ghost shark species often caught off New Zealand: the brown chimaera and black ghost shark. The team examined hundreds of deceased individuals, including museum specimens and animals recently hauled up in bottom trawls.

Study leader Brit Finucci, a Ph.D. student at Victoria University of Wellington, and colleagues studied fish at various stages of sexual maturity, weighing and measuring various parts of their anatomy.

Like many shark species, female ghost sharks have two sets of working uteri, two sets of ovaries, and a pair of egg passages. The males’ forehead sex organ has hooks that they may use to clasp onto the fins of the females during mating, and two other clasper organs around their pelvis for the actual copulation.

Mating “does not seem to be a very pleasant experience for the females,” Finucci notes.

Food and Sex

The special sperm storage area in brown chimaera females’ reproductive tract is the same structure Finucci recently discovered in two other ghost shark species, which are sometimes called spookfish. The chimaeras keep the sperm, densely packed, within several tiny tubes of their oviducal gland.

“There’s a good chance that these animals breed in one place at one time then lay their eggs at a different time,” says Finucci, whose study was published recently in the Journal of Fish Biology.

That ability is crucial in the deep ocean, she says, where food and mates can be hard to come by. For this reason, Finucci believes sperm storage is likely practiced widely among ghost sharks.

It’s unknown how long ghost shark females hold sperm, but captive bamboo sharks can do it for over three years—suggesting that ghost sharks can as well, she adds.

The team made another discovery: An organ on the roof of the mouth of both sexes that may help them find food in the dark, muddy depths.

Scientists first identified this palatal organ in the monster ghost shark in 2015. “It’s a fleshy organ, rich in nerve endings, taste buds, and multicellular glands,” Finucci says.

Though much is unknown about ghost shark diets, Finucci says they’ll eat pretty much anything they come across. “There are some videos out there where you see chimaeras essentially face-planting in the sand, which may be how they forage.”

Mysterious Sea Creatures

The research also revealed that brown chimaera and black ghost sharks are relatively rare compared with other ghost sharks in New Zealand waters; large, reproducing females are even rarer.

Scientists are unsure whether this is due to low numbers, or if they just don’t know where to look.

After all, chimaera are still mysteries to science: Nearly 40 percent of chimaera species have been revealed only in the past 15 years or so, says Ebert.

Though more is emerging bit by bit—the first-ever video of the pointy-nosed blue chimaera was released in 2016, for instance—scant evidence exists of the creatures in the wild.

“They are literally a whole group of fishes that we know almost nothing about,” says Ebert, who wasn’t involved in the new research.

“Brit’s study is one of the few that tried to look at the life history.”

This article was first published by National Geographic on 12 Jun 2017.

Leave a Reply