Recently, wildlife news from Africa has been almost universally bleak and frustrating to the point of despair: rhinos with their faces cut off, elephants slaughtered en masse via helicopter, and chimps and gorillas gunned down or snared for bushmeat.

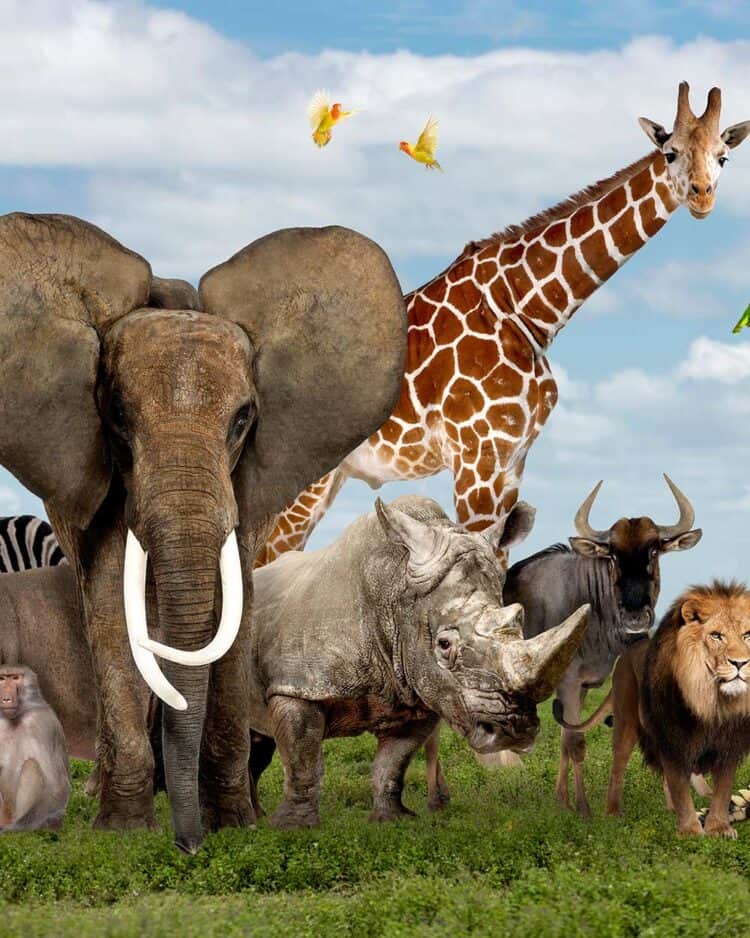

A massive onslaught of people, poaching and habitat destruction has led to declines in everything from lions to giraffes and hippos to okapi. But this picture of blood, carcasses and seemingly relentless loss isn’t the only reality on a continent three times the size of Europe.

There are still places where wildlife runs largely unmolested, where abundance is unquestionable, and where wilderness covers an unbroken horizon: one of these is Botswana’s Okavango Delta.

“The Okavango Delta is the largest, most important Ramsar site in the world – one of the last, great wetland wildernesses on the planet,” said Steve Boyes, a National Geographic Explorer and renowned bird expert, referring to the international Ramsar treaty for the protection of the world’s wetlands.

“Visible from space, [it] is the jewel of the Kalahari Desert, an emerald gem that supports an abundance of life,” he added.

But while the Okavango Delta has been well surveyed, its main source rivers have not. The Cuito and Cubana Rivers begin nearly two thousand kilometres away in the highlands of Angola, a region that has been long-veiled by a 27 year civil war. The brutal conflict ended in 2002, but the area is still riddled with its scars, including broken down tanks, crumbling buildings, and, worst of all, fields of unexploded land mines. Not surprisingly, scientists and conservationists have stayed away.

But a new National Geographic expedition headed by Boyes – Into the Okavango – is currently running the full length of the unexplored Cutio River in order to bring attention to its importance for the survival of the Delta.

A ‘first’ expedition

Boyes’ team, which started out on May 21st, has already begun moving downriver on the Cuito. Over 90 days and 1,900 kilometres, they intend to travel the entirety of the river, cross the sprawling Delta and end in the hot salt plains of the Makgadigadi Pans.

James Kydd, the expedition’s photographer, called the journey “the first of its kind ever attempted… from ‘source-to-sand.’”

The explorers are live tweeting their journey, including sharing photos, videos, interactive maps and even animal sounds, recording every species they encounter in real-time.

“Social media has made an expedition like this, traditionally only for scientists, something the public can actively get involved in and help drive,” noted Kydd. “The more eyes fall on this expedition, the more likely protection will be committed to this great wilderness.”

Although the team will be using the latest in technology to bring their expedition to the world, the basics of the expedition are decidedly low-tech.

“On land, armed only with spears, we will be conscious of every step, mindful of snake, lion, buffalo or numerous other potential dangers including human,” said Kydd. “We will also be interacting with whatever people we encounter along the way, some the direct descendants of the ancient San people hoping to share stories and understanding of the river. We will eat water lily bulbs and fish, and listen to the Tswororo, the traditional melody of our compatriot Ba’Yei.”

The Ba’Yei are the traditional people of the Delta, who have long used dugout canoes – known as mokoros – to survive in the watery landscape. The team will be travelling on these mokoros – far more flexible than motorboats – propelled by Ba’Yei expedition members.

The journey will result in a feature story in National Geographic, a documentary and a book. But, most of all, the team hopes their efforts will push policymakers to protect the Okavango’s source waters in Angola, which Boyes called “a landscape unseen by science and last explored by non-military personnel almost 100 years ago.”

The kinda famous Okavango Delta

Although well-known to researchers, conservationists and even some intrepid tourists, the Okavango Delta does not have the same international profile as many other African wildernesses, such as the Serengeti and the Congo. Still, Kydd said the Okavango Delta is arguably the continent’s most pristine wildlife area.

“There is no wilder place on Earth: this is the Africa of a hundred thousand years ago.”

Elephants illustrate this point. The team estimates that the Delta is home to around half of the continent’s elephants. Indeed, a recent survey by the Great Elephant Census counted 129,000 elephants in northern Botswana.

Moreover, compared to most regions of the continent, elephants are relatively safe in the Okavango. The most recent census found no evidence of poaching. Researchers also believe that more elephants are moving into the Delta from neighbouring countries. These are psychologically-scarred immigrants fleeing poaching hotspots.

The landscape is also home to key predators like cheetah, African wild dog, leopard and lions – many of which have vanished or crashed in other protected areas. The Delta is also the global stronghold for the red lechwe, a water-loving antelope.

Rhinos are even making a comeback here, after nearly being wiped out in the last poaching epidemic of the 1980s and 90s. Desperate to save black and white rhinos from the poaching crisis in South Africa, conservationists have begun moving small populations to the Delta for safe-keeping.

This doesn’t mean that the Okavango Delta is wholly immune to the threats present in other African wilderness, such as habitat fragmentation, deforestation, human-wildlife conflict and poaching. Indeed another survey in 2011 by Mike Chase found that some populations of animals had crashed in the delta, most particularly wildebeest, ostrich, giraffe and several antelope species. However, scientists suspect the largest driver behind these drops was cyclical drought.

Although still a place of incredible abundance, the Okavango Delta remains somewhat obscure. Its humble place on the world stage may be best illustrated by the fact that Botswana only nominated the site for UNESCO World Heritage status in 2013. Last year, the committee approved the request, making the Okavango the world’s 1,000th World Heritage site.

The other end of the Okavango: bloodied Angola

However, the Delta’s wildlife riches and political stability couldn’t contrast more sharply with the Angolan highlands. And even as the Okavango Delta may not be as famous as it should be, the Angolan highlands remain wholly obscure.

Boyes called the Angolan highlands “a landscape preserved in time by war, blood diamonds and instability” where the “deep Kalahari sand” makes vehicle travel so difficult that the “war was fought on foot and using helicopters.”

The quarter century conflict left an estimated half-million people dead and an additional million displaced. And it’s still killing people today.

“The people along the [Cuito River]…have to exist with the constant threat of a mine going off,” noted Boyes, whose expedition could only make their way to the river after a route had been cleared by the de-mining NGO, Halo Trust.

The war also decimated the country’s once great wildlife spectacles.

“Almost 30 years of civil war and border wars depopulated the landscape, leaving it with one of the world’s highest concentrations of land mines and very few animals,” said Boyes, who noted that the region suffered both from deforestation and poaching during the long, internecine conflict.

But, he added, there are signs that after more than a decade of peace, wildlife are beginning to return. For example, he said “elephants are slowly coming back [to Angola] as de-mining NGOs and government agencies lift the curtain of mines.”

As the team makes their way further down river, they may uncover a lost world.

“We hope to rediscover the Angolan lion, wild dogs, elephant, buffalo and cheetah,” said Boyes. “We are expecting to find new species of fish, dragonflies, reptiles, plants and even birds and mammals. We are looking for the first confirmed sightings of wattled crane and slaty egret [in Angola], as well as the first records of crocodiles breeding along the river system in Angola.”

He added that the local governor told the group the Cuito River “has the highest density of crocodiles in the world.”

Already, the team has uncovered lion and leopard footprints, heard bushbabies, found evidence of pangolins and listened to a strange story about a mystery antelope that plays dead to avoid predation.

Conservation goal

The transnational journey by mokoro is not just about scientific discovery, though. Arguably more important is harnessing the political will, both locally and internationally, to protect the long-neglected Angolan highlands. Not only are the highlands unprotected at the moment, but they are not even included in the UNESCO listing.

Steve Boyes talks about the importance of the Okavango Delta.

“If the river upstream of the delta in Angola is not protected, the consequences for the Okavango Delta, its people and wildlife could be catastrophic,” said photographer, James Kydd.

Boyes added that the team is pushing for a “a multinational World Heritage Site that includes the rivers that sustain the Okavango Delta.”

If the listing expands to include the Angolan highlands this could also help drive tourism – and international funding – to the forgotten part of the world.

“We need to act now to save this river before it is too late [from] charcoal production and ill-planned agriculture and mining,” said Boyes, who noted that people were returning to the river now that the war has ended.

“Economic development is incredibly important, but we need to make sure the Angolan government has all the information they need for decision-making,” he added.

Even more than the Okavango Delta is at stake in the highlands, though. Boyes said the region should be known as the “water tower of southern Africa,” since, in addition to providing the origins of the Delta, the region also sources such vital rivers as the Zambezi, which includes Victoria Falls, and the Lomami River, a major tributary in the Congo Rainforest.

Although the team expects the expedition to be gruelling – “days of dragging our mokoro through muck, sharp reeds and leeches,” said Kydd – it will all be worth it in the end.

“We will share great camaraderie, and in the Delta we will experience the tear-jerking beauty of Africa’s greatest wilderness.”

And if the team can succeed in protecting the Angolan highlands, the Okavango Delta has a chance of remaining just that.

This article was first published by The Guardian on 28 May 2015.

Leave a Reply