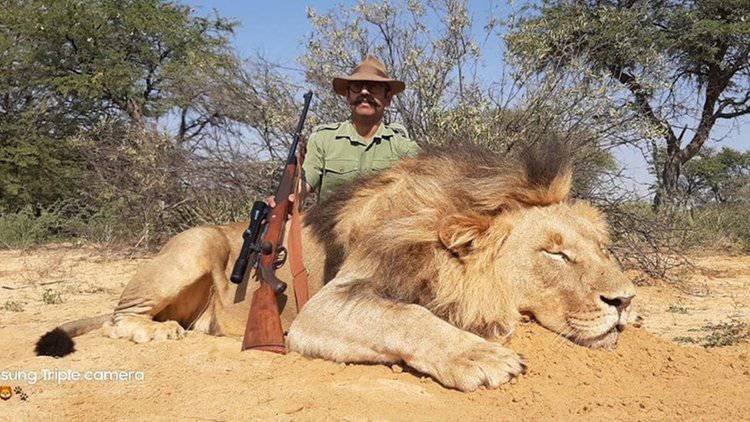

Up to 7,000 lions are living behind bars in South Africa. Raised in captivity on private breeding farms and hunting “reserves,” some of these animals are petted as cubs by tourists, who can also walk alongside or even feed more mature lions.

Eventually, many are shot in “canned” hunts, in which lions are pursued and killed in confined areas that make them easy targets. Hunt fees can be as high as $50,000.

The hunters take lion skins and heads home as trophies. Lion bones and bodies are exported to Asia for traditional cures.

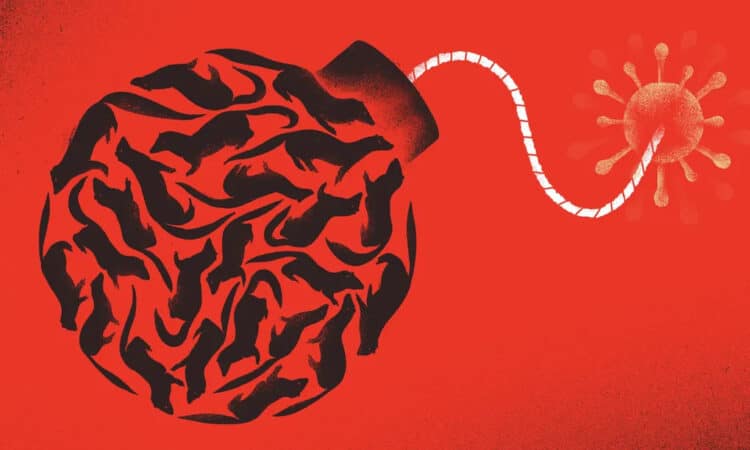

As new measures are put in place to clamp down on trade in the bones of endangered tigers, the lion bone trade grows. Substituting tiger with lion bone means that lionesses, as well as trophy males, now have commercial value.

The new documentary Blood Lions lays bare the dark underbelly of South Africa’s captive breeding and canned hunting industries. The film will be screened in Durban, South Africa on Wednesday at Africa’s leading film festival.

Owners of private breeding farms say that more hunting of captive-bred lions takes pressure off declining wild lion populations.

Not so, says Dr. Luke Hunter, president of Panthera, an organization dedicated to conserving endangered big cats. “This industry pumps out cats to be shot in cages or shipped to Asia to supply the demand for big cat parts. Blood Lions blows away the hollow ‘conservation’ arguments made by South Africa’s predator breeders to justify their grim trade.”

Blood Lions joins other films, like Gorillas in the Mist, Echo of the Elephants, The Cove (Taiji dolphins in Japan), Blackfish—that Born Free Foundation president Will Travers says “have truly influenced the way we interact with wild animals.”

From his home in South Africa, Ian Michler—the film’s protagonist and narrator, who has spent 25 years across 15 African countries as a specialist safari operator, journalist, and conservation advocate—talks about lions, the making of the film, and what reforms he hopes it will spur.

How did you come to defend lions?

When I was living full-time in the Okavango Delta in the 1990s, guiding and managing lodges, I became interested in the sustainability of lion hunting in Botswana. This led me to finding out about farms in South Africa and canned hunting.

In 1999, there were between 800 and 1,000 lions in cages. When in 2005, I submitted a report to the minister of environment and tourism, there were between 3,000 and 3,500 captive lions. Now there are some 8,000 captive predators—lions, tigers, leopards—in my country. Of these, the majority are lions.

Clearly, the industry—which is very lucrative for a small number of individuals—has grown and continues to grow. Critics are told that these facilities exist for education and conservation purposes.

However, these quick justifications have no evidence base. Lions are among species that cannot be re-wilded after being hand-reared. No South African ecologist is currently trying to reestablish lion populations—and if they were, no one would use captive-bred lions anyway. It’s false marketing!

These majestic predators are being raised in captivity to be shot in captivity. And to me—and a growing number of people across the globe—this is unacceptable.

How do South Africa’s lions differ from those in other African lion range states?

South Africa is the only country in the world that has three classes of lions. Lions in South Africa can be “wild,” “managed,” or “captive.”

According to credible organizations like Panthera, South Africa has between 2,700 and 3,200 “wild” and “managed” lions—split roughly 50/50. The wild lions live in two parks, Kruger National Park and Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. Managed lions inhabit private reserves such as Phinda and Tswalu and are managed in the name of keeping the gene pool diverse.

The South African Predator Association (SAPA) keeps track of captive lions and captive breeding facilities, but not everyone who breeds lions in South Africa has to be a member, and not everyone who is provides real statistics. In our estimate, based on interviews we’ve done with SAPA, and also with the department of environmental affairs, some 7,000 lions live in captivity.

What is the narrative thrust of Blood Lions?

It’s about exposing the industry and its fallacies, and the revenue streams that have evolved. The film is balanced, in that 40 percent of it is dedicated to the breeders and hunters themselves, who get to have their say.

Does “fair chase” hunting still take place in South Africa?

Fair chase hunting is the traditional form of trophy hunting wherein the animal being pursued has a fair chance of escape. These hunts take place over an extended period of time and on foot. In canned hunting, the hunter is guaranteed a kill.

Fair chase does still exist—in Tanzania and Zimbabwe, and to a lesser extent in Namibia, Zambia, and Mozambique.

In a progressive move, Botswana banned trophy hunting in 2014.

In South Africa, with the proliferation of breeding farms, and the surging wildlife trade industry, there’s very little fair chase hunting. I would say almost all is now of a canned nature.

What’s the likelihood of “fair chase” hunters opposing lion breeding and canned hunting practices?

All professional hunting bodies have ethics in their chapters and claim to have an ethical and conservation approach to what they do. If hunters were to practice this, they should be supporting us. Most, however, seem to be against closing down predator breeding.

The Professional Hunters’ Association of South Africa sides with breeders and canned hunters. They’ve tried to make the practices more palatable by claiming that canned hunting no longer exists. This, they say, is because bait and tranquilizers are no longer used. In a play on words, they now call what they do ‘captive hunting.’ But whatever name is used, canned or captive, it’s the same thing.

There are professional trophy hunters beginning to oppose this, including operators based in KwaZulu-Natal. One such group is SAMPEO, and they will play a major role in our campaign.

What changes do you hope Blood Lions will bring about?

The end of exploitative breeding of lions and other predators and the closure of canned hunting.

We reached Australian (and American) audiences with a promo clip that we used to raise money to get the documentary made. Some of this promo was fortuitous in that an Australian organization called For the Love of Wildlife saw the clip and took it to their Parliament, from where it made its way to the minister of the environment. It caused outrage.

Australia’s lion trophy ban came about because the Australian government was incredibly proactive. And also because Australians make up a relatively low proportion of trophy hunters, so the decision to ban lion trophies was not going to affect a large constituency.

In the EU, there are strong rumblings of positive change thanks to the Trophy Free EU Group, MPs for Wildlife, and the European Citizens’ Initiative.

But more than 50 percent of trophy hunters come from the United States. My question to these hunters is: If you are against these practices, then speak out to help stop them.

And young people who come to South Africa to volunteer in lion facilities: please be aware as you’re in all likelihood being scammed into paying significant sums of money to inadvertently help raise cubs that will later be shot.

Finally, I’d also like to raise the ethical discussion around how we treat other animals. We’ve been railroaded by economics and other justifications. I urge that we take our updated knowledge of animal welfare, of how ecosystems work, and the interrelatedness of it all, and adjust our behavior accordingly.

This article was first published by National Geographic on 22 Jul 2015.

We invite you to share your opinion whether lion canned hunting should be banned? Please vote and leave your comments at the bottom of this page:

Thank you for voting.

Leave a Reply