Six whales have washed ashore in northern California in the past two months, prompting headlines around the world and attracting droves of tourists, curious about the massive mammals so suddenly out of their natural element.

According to a California Academy of Sciences (CAS) necropsy one of those whales, a 32ft female humpback that washed ashore in Pacifica, a 20-minute drive from San Francisco, had “signs of trauma consistent with blunt force”.

Suggested causes of death have included being hit by a ship and an attack by an orca. But while those might have been the final blows for the whales, other issues are being raised by environmental groups such as Earthjustice, the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Greenpeace. These issues include the US navy’s use of sonar.

Moe Flannery, a stranded marine mammal responder and manager of the CAS Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy, declined to give a cause of death shortly after conducting the necropsy on the first Pacifica whale. But she did say the whale showed signs of muscle hemorrhaging, an injury which research has shown to be consistent with sonar-related deaths.

Other researchers who participated in the necropsy, including those from the Marine Mammal Center (MMC), corroborated such findings and pointed out that hemorrhaging does not necessarily mean blunt force trauma from a ship. The MMC, which is currently focusing most of its resources on the problems facing starving sea lions, declined to comment on whether sonar was involved.

Although it is difficult to determine sonar-related injuries and deaths, Earthjustice attorney David Henkin argues hemorrhaging should not be used as a reason to dismiss sonar as a potential culprit. Possible evidence of sonar contributing to whale deaths, such as emaciation, hemorrhaging and bleeding of the brain, was present in the Pacifica humpback stranding and in stranding in Santa Cruz of two grey whales.

“That difficulty [in determining cause of death] should not be misinterpreted as raising questions about whether sonar is a likely cause of many strandings and associated marine mammal deaths,” Henkin said.

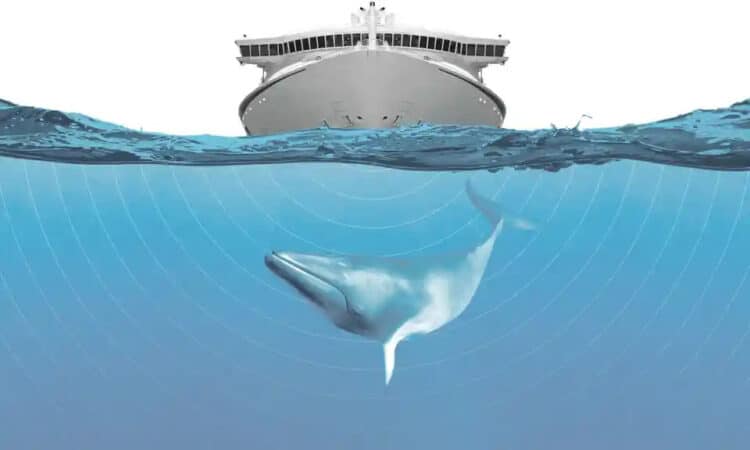

According to the NRDC, a non-profit that seeks to protect wildlife, sonar can be devastating to whales and other marine animals that rely largely on hearing to complete daily functions, including orientation and communication. Without the ability to hear, it is difficult for whales to “find their way through the world every day”, the organization says in a fact sheet.

In March, a US district court in Hawaii found that the National Marine Fisheries Services (NMFS) improperly gave approval to the navy’s use of sonar in the Pacific, an issue long-contested by environmental groups that allege sonar is causing damage to marine animals’ migration patterns, feeding locations, breeding and ability to hear and communicate. The navy uses sonar for training, to simulate real-life situations in the ocean. Thousands of sonar devices remain in the coastal waters of the Pacific as Earthjustice and other environmental organizations negotiate with the navy on how and where it should use sonar for drills.

“Like so many things in life, it’s not what you do, it’s how you do it,” said Henkin when discussing the ongoing negotiations with the military. “The most serious harm to marine mammals occurs when sonar use is in close proximity to animals … Thus, the focus of our efforts has been on minimizing and, where possible, eliminating, sonar use in areas identified as biologically important to marine mammals.”

The Hawaii court said that it found numerous problems with the justifications NMFS gave in authorizing the navy’s sonar program. Chief judge Susan Oki Mollway delivered a written ruling, which bordered on bewilderment.

“Searching the administrative record’s reams of pages for some explanation as to why the navy’s activities were authorized by the National Marine Fisheries Service,” she wrote, “this court feels like the sailor in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner who, trapped for days on a ship becalmed in the middle of the ocean, laments, ‘Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink’.”

The navy is not being forced to stop using sonar, says Henkin – it is only a matter of where and how. The navy requires authorization from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The navy’s current five-year permit expires this year.

Linking strandings to sonar is a challenging and often impossible task, but previous incidents can give clues. A 2006 report published by NOAA and the NMFS reported that the stranding of over 100 melon-headed whales was “likely” the result of sonar training having been conducted in the area. The sonar testing forced the animals to change their normal migratory patterns, which resulted in at least one calf dying from dehydration. The report linked the death directly to the sonar testing.

The navy did not respond to requests for data on recent sonar training drills along the California coast. But the navy uses powerful sonar for nearly 12,000 hours a year in the Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing Study Area. For all types of sonar combined, the navy uses more than 50,000 hours a year. It cites national security as a reason to continue the practice and training exercises.

In a May 2012 report on sonar use, the navy said acoustic sources and sonar more than 2.5 million times annually exposed marine animals to sounds considered “disturbing”, while around 500 times a year marine animals were exposed to sound levels that were considered to result in injury.

Sonar is designed to create an echo through the water. This is then bounced back to the emitting vessel in order to determine if another vessel is in the water, such as a submarine. For marine animals, especially whales and dolphins, sonar creates sound waves that reflect back and forth much like an echo in a canyon. This can disrupt their ability to communicate and locate food sources.

Greenpeace reports that seismic occurrences in the ocean, including sonar, can result in the “temporary and permanent hearing loss, abandonment of habitat, disruption of mating and feeding, beach strandings and even death”.

Sonar is not the only noise-making culprit that has scientists worried about marine life. In a recent report on Shell’s exploration efforts in the Arctic, activities such as drilling, seismic testing and ice-breaking activities were said to expose whales to damaging sounds.

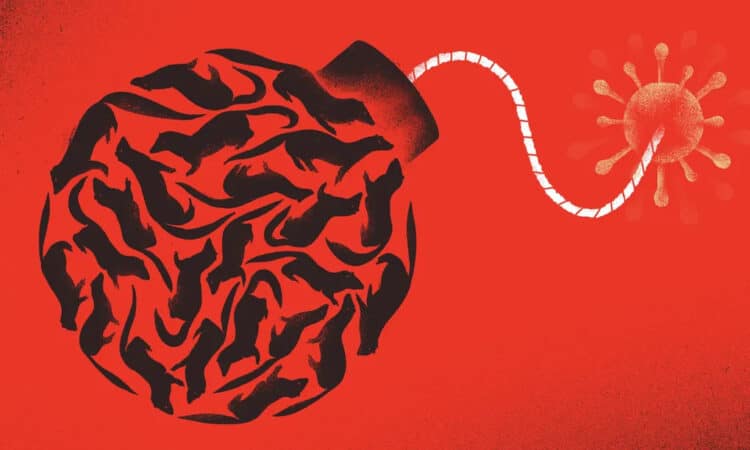

Tim Donaghy, a senior research specialist with Greenpeace, said “a deaf whale is a dead whale”, referring to a study by Oceana from 2013.

While sonar may never definitively be named as the cause of the whales’ deaths, it is having a direct role in changing marine ecosystems.

According to a Monterey Institute primer, titled Noise Pollution and Whale Behavior: “Whale sonar allows the animals to find food, safely travel along irregular coastlines, and migrate to and from breeding and feeding grounds. Some whales uses bursts of loud noise to drive and confuse their prey.”

“These activities are becoming more and more difficult as manmade noise in the sea has increased dramatically. Ship traffic, oil and gas exploration, scientific research activities, and the use of military sonar and communications equipment have caused an increase in ambient marine noise of two orders of magnitude in the last 60 years.”

The World Wildlife Fund reports that marine life is migrating to different waters as climate change’s effects on the ocean’s biodiversity take hold, disrupting centuries of established norms.

“Even when stranding does not result, military sonar can cause hearing loss and internal injuries to marine mammals that results in death, even if the animal does not end up on shore,” Henkin said.

“Indeed, it is because most deaths associated with military sonar are never observed that both NMFS and the navy use modeling to determine likely harm to marine mammals.”

The editorial content of this article was first published by The Guardian on 14 Jun 2015.

We invite you to share your opinion whether stricter sonar controls should be imposed on the US navy? Please vote and leave your comments below:

In the event that you voted for the imposition of stricter sonar controls on the US navy, please sign the petition:

Leave a Reply