The Maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) is by all accounts a bizarre creature. Nicknamed a “fox on stilts,” it is perhaps best known for its once-heard-never-forgotten “roar-bark.”

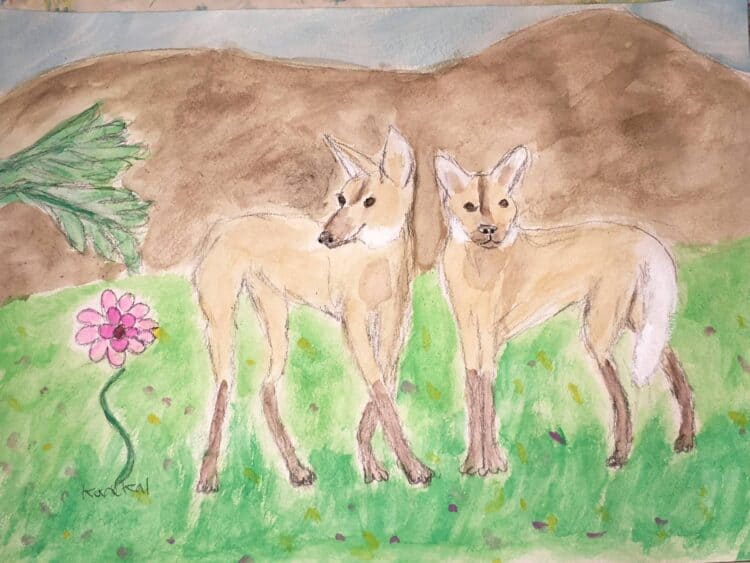

A single look at this strange, gangly and rather scruffy creature, with its bobbing gait and bat-like ears — with the body of a wolf, face of a fox, legs of a deer, and urine that smells like marijuana — and you might be left puzzled as to why you’ve never heard of it.

Classified as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Maned wolf dwells mostly in the Cerrado — the vast savanna of Brazil, though it is also found in the pampas of Peru, and the scrublands of Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The current population of Maned wolves is estimated at 17,000 mature individuals, with the majority of the population — more than 90 percent — in Brazil, says the IUCN. In the last decade or so, the species’ main habitats have been subject to intense deforestation.

In addition to habitat loss, the species is subject to other serious threats, including road kills, direct persecution by humans, and disease due to contact with domestic animals

Still the Maned wolf hangs on — traveling not in large packs, but as lone wolves roaming a vast territory once dominated by wild grasslands, now cultivated in exotic eucalyptus, pine, soybean and sunflower plantations.

The Cerrado: home to the wolf

The Amazon region, with its extraordinarily rich abundance of wildlife, has understandably been at the center of South America’s biodiversity spotlight for decades — unfortunately, leaving the animals that dwell outside of it in the shadows, cast as second class species, and ignored by the media and the public.

One such largely ignored region is Brazil’s Cerrado, and one such species is the Maned wolf.

Few people are fighting to save Brazil’s sprawling savanna, or its unique species, today, despite it being labeled as a key global biodiversity hotspot by conservationists. For Rodrigo Lima Massara, a biologist at Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, the attention given to the Cerrado is inconsistent with its biological importance. He has dubbed it: “the world’s most biologically rich savanna”.

The Cerrado is also under far greater threat than its more illustrious rainforest neighbor; in 2009 the Brazilian government reported a deforestation rate of 0.14 percent in the Amazon, while in the Cerrado, the figure was over double that at 0.32 percent.

While that is bad news for the Maned wolf, it may not be quite as bad as it sounds.

In 2012, Massara conducted a study, published in Mongabay’s open access Tropical Conservation Science journal, that suggests rampant deforestation may not be as catastrophic to Maned wolf populations as expected.

“Despite the diversity of impacts and the constant presence of humans, vehicles and domestic dogs in the study area, the Maned wolves are there,” the study says. Still, when it comes to the species’ potential adaptive abilities to human pressures, Massara and his colleagues have adopted “cautionary skepticism”.

“Although conservation may not be such a pressing issue for the Maned wolf, we don’t know how the current rate of deforestation can affect the species in a near future,” he told mongabay.com. A lack of research and data concerning population sizes, genetic health and more, rules out overly optimistic conclusions.

The study concludes that the Maned wolf will require a created system of natural ecological buffer zones if adequate food supplies are to be maintained for remaining populations, and to ensure continued survival.

Unfortunately, little or nothing has been done to create these natural buffers. “Actually, recent changes in Brazilian environmental legislation may worsen this scenario,” Massara said, referring to alterations made to the Brazilian Forest Code that scrapped plans to restore areas illegally deforested before 2008. The changes to the code will decrease the amount of land cover designated for reforestation in the Cerrado significantly.

“At the same time, this new Forest Code removed protections for other natural areas in the Cerrado, allowing farmers and ranchers to deforest and convert some of these areas,” he explained. The new Forest Code has already allowed 400,000 square kilometers (154,440 square miles) to be converted to agricultural lands.

A different kind of wolf

The Maned wolf suffers from more than habitat loss. It has been saddled with a rather simple but quite formidable problem: its name.

While its moniker suggests otherwise, the Maned wolf isn’t actually a wolf at all. While it looks like a fox, and is called a wolf, it’s actually more akin to a wild dog. In keeping with its solitary nature, it also has a genus, chrysocyon, all to itself.

The Maned wolf is different in many ways from its northern namesakes. Whereas other canids are polygamous, taking more than one mate in their lifetime, the Maned wolf is monogamous. It is also a solitary wanderer, and never travels in packs as do the wolves of North America. As the tallest of all canids, the Maned wolf has evolved extremely long legs which help to lift its head above the tall grasses through which it moves.

Distancing itself even more completely from its North American counterparts, a large portion of the Maned wolf’s diet is actually made up of fruit. Solanum lycocarpum — also known as ‘wolf’s fruit’ — is a favorite meal of the Maned wolf and its preservation in natural buffer zones is crucial to the wolf’s conservation.

Aside from its bizarre appearance, its unfortunate name and its curious eating habits, the wolf also has a rather peculiar vocalization, known as a “roar-bark”.

“I first heard it in the distance, [and it was] unlike anything I heard before coming from a canid,” Dr Adriana Consorte-McCrea, a research fellow at Canterbury Christ Church University, told mongabay.com.

She explained that the unique Maned wolf call is amplified as the mating season approaches, suggesting the sound is closely linked to courtship and the defense of territory. “It sounds a bit like a large dog coughing, with a very steady, spaced rhythm,” Consorte-McCrea said. The scientist was so captivated by her early meetings with the Maned wolf, that she decided to devote much of her career to researching it, publishing several studies and a book on the species.

Living with the wolf

Much of the researcher’s work has focused on the evolving perception of the Maned wolf in the eyes of those who live with it. She connects many of the problems it suffers today to its history, and to the unfortunate name it has been burdened with during the historical period.

According to Consorte-McCrea, the indigenous people who lived with the Maned wolf prior to colonization respected it, telling “beautiful stories” about the fruit eater with the curious roar-bark.

Not so the colonists who settled the Cerrado. “Any wild animalin European coloniesthat had the misfortuneof looking like a ‘wolf’wascursed from day one!” explained Consorte-McCrea. “Portuguesecolonizers brought with them — and attached to the Maned wolf — all the stigma of a ‘livestock holder’s worst enemy’ that had cost many European wolves their lives,over many centuries.”

That erroneous guilt by association with Europe’s wolves, has remained prevalent down to the present day.

“The relationship between people and Maned wolves seems to be immersed in many misconceptions about the wolf’s diet, ecology, and behavior, and surrounded by mystical beliefs,” Consorte-McCrea writes in a study that gauged public opinion of the Maned wolf in Brazil by surveying zoo visitors.

She found that although most people questioned viewed the Maned wolf favorably, they also held a strong belief that its favorite food is chicken, a troublesome misconception with “important conservation consequences.”

Retaliatory killings of Maned wolves continue to occur in the Cerrado, despite the fact that the hunting of the species is illegal throughout its range. Although cases where Maned wolves take chickens do occur, the fear is far overblown, according to Consorte-McCrea.

“Vast studies of Maned wolf feeding ecology show that traces of chicken are found in less than one percent of wolf feces,” she said. In fact, rather than being livestock predators, the animals have an important part to play in farm pest control. The average Maned wolf consumes up to 65 rodents for every chicken it eats. “I would be thanking them, if I were a farmer!” she exclaimed.

Consorte-McCrea believes that correcting this misconception will likely be crucial to conserving the Maned wolf in the wild.

As it stands today, there are no concerted efforts focused on the conservation of the species. A region-wide, 2005 Population and Habitat Viability Assessment workshop for Maned Wolves did generate an International Action Plan aimed at addressing the main long-term conservation concerns for the species, including threats to habitat; assessment of distribution and status; environmental education; and ex-situ conservation. But implementation of the plan has been limited.

About the only major assist the animals get from humans is from those who seek to protect what remains of the Cerrado native habitat, which indirectly aids the besieged Maned wolf. But that is not enough: the species is expected to suffer a ten percent decrease in its numbers in the near future if its habitat continues to shrink.

“Over-exploitation of natural resources is a very short sighted… way to generate income,” Consorte-McCrea said bluntly of the continuing transformation of native savanna into agricultural lands. The Brazilian government has supported the Maned wolf by classifying it as Vulnerable, but it has also failed to crack down on the loss of Cerrado habitat, accelerating habitat loss with its new federal land use and forests policy.

Consorte-McCrea declared that if the Maned wolf is not protected, much more than a wild dog will be lost. “They are part of these [South American] countries’ heritage, and the result of millions of years of evolution… it would be a crime and a mistake, with no return, to losethem forever.”

If the Maned wolf is not protected, then one of nature’s quirkiest creations — a dog that looks like a fox, and walks like a deer, and sounds like well, a Maned wolf — will be consigned to history.

This article was first published by Mongabay.com on 07 Dec 2015.

Leave a Reply