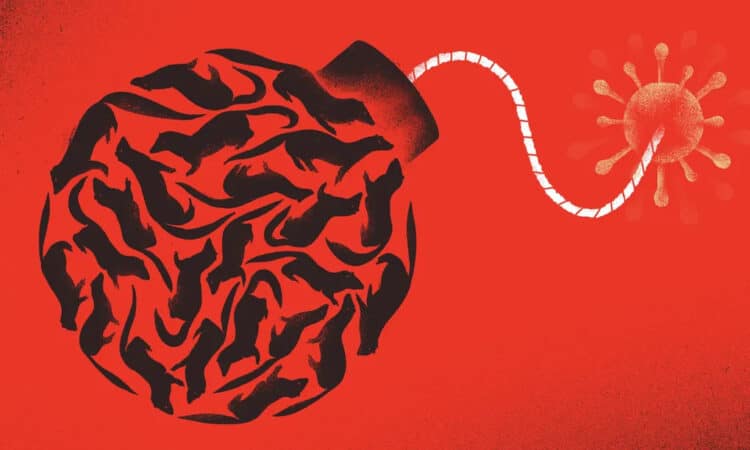

Are you neurotic about all things zoonotic? Perhaps you should be. A new strain of bird flu, H7N9, has recently emerged and has killed more than 30 people in China to date. There are concerns that this flu may mutate into a form that can be transmitted through human-to-human contact, risking its transformation into a pandemic disease. But before we consider that scenario, let’s back up a little bit.

Zoonotic diseases are infectious diseases that arise in other animals and infect the human animal. That is to say us. Of the nearly 1,500 pathogens known to infect humans, more than 60 percent are zoonoses. Wild birds are reservoirs of many types of avian flu. The new (new to infecting humans, that is) H7N9 is one of them. The avian flu scare of a few years ago, H5N1, accounted for more than 350 human deaths. It is still around.

Perhaps you have heard of the Spanish Flu. If you watched Downton Abbey, you recognize it as the plot device that brought together Lady Mary and Matthew, whose fiancée succumbed to this illness upstairs while he and Mary danced downstairs. What you likely do not know is that Spanish Flu killed around 5 percent of our total human population across the globe — some 50 to 100 million people — between 1918 and 1920.

Zoonotic illnesses emerge as we continue to crowd nature, bringing people and wildlife ever closer together. With the loss of wild habitat, we see more mingling of birds, humans, and our domesticated animals. Disease transmission from wild birds to domestic waterfowl and poultry is common. H5N1 spreads to humans in large part through exposure of Asian farmers to both their own poultry and those found at markets.

Avian flus are a major group of zoonoses, and are most commonly found in waterfowl and other water birds. While H5N1 has not yet mutated into a form that transmits between humans, the Spanish Flu did, causing the massive epidemic a century ago. Fortunately, the H7N9 virus is not yet known to do so.

With the appearance of this new virus, the global health staff of the Wildlife Conservation Society quickly determined the flu’s prevalence in global wild bird populations and ruled out wild birds as the immediate reservoir of flu causing human cases. The use of wild bird tissue samples collected during the H5N1 outbreak helped facilitate those findings.

That determination demonstrated that the H7N9 flu was rare everywhere and the emerging human infections in China were more likely to be from poultry (as infections from its cousin H5N1 had been). The discovery was important, as it meant that widespread slaughter of wild birds was unnecessary. What was required instead was the use of better management practices by poultry farms and markets.

I was a small part of the H5N1 surveillance a few years ago in Arctic Alaska and in South Korea. In Alaska our field crews captured shorebirds, swabbed their throats, and took blood as part of a much larger effort to see if the H5N1 outbreak involved migratory birds. Because several migrants come to Alaska from wintering areas in Asia, the concern was great.

There was a risk that migratory wild birds from Asia, infected with H5N1, could be mixing with migrants arriving from the Americas on the massive Arctic breeding grounds. Such a scenario could have led to transmission of the virus widely.

As it turned out, that surveillance project determined that the highly pathogenic H5N1 was not coming from Asia, and thus not a risk to the New World. The spread then and now was limited to poultry, facilitated not by migration but by commerce (as H5N1 continues to spread in the Old World).

In the spring of 2008 we surveyed Arctic-bound shorebirds along the coast of the Yellow Sea in South Korea. Concerning us chiefly were Dunlin and Bar-tailed Godwit — two shorebirds we know well from our studies in the Arctic coastal plain of Alaska.

It happened that our field efforts in South Korea coincided with their worst poultry outbreak of avian flu. The military destroyed millions of poultry. The government set up sanitizing spray stations along the main highways and an outraged, neurotic populace threatened the presidency. The wild shorebirds we caught and sampled proved negative at a time when the poultry were infected and people were at risk.

How and where will the new bird flu fly? Will it grow or be contained? History offers different outcomes, yet we do know for certain that zoonotic diseases will continue to emerge.

This article was written by Steve Zack for the HuffingtonPost.com

Leave a Reply