For more than a decade, I’ve been blathering on and on about todies. For a time, if you googled “Most adorable bird in the universe,” the first page you got was from one of my blog posts about the Cuban Tody.

It really does live up to those words, but unless you’re an ornithologist or know enough Latin to recognize that todus means a small bird, you would likely have trouble looking up the word tody, because its homophone is in much more common use. I asked my iPhone what a tody is, and Siri said, “Tody means a person who behaves obsequiously to someone important.”

When I asked her how to spell tody, she responded, “T-O-A-D-Y.” Every time I write the word tody using Microsoft Word, I’m told I’m misspelling it, and given the suggestions toddy, today, tidy, and toady, spelled the way Siri spells it.

That would be all well and good if I wanted to write about sycophants, but Siri is clearly not a birder. Tody in my world is spelled T-O-D-Y, and refers to a bird family,Todidae,in the order that includes kingfishers and motmots.

This family includes just one genus, Todus,that includes five tiny species, all found only in the Greater Antilles, each endemic to one island. There is one tody each on the islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica, and two on Hispaniola.

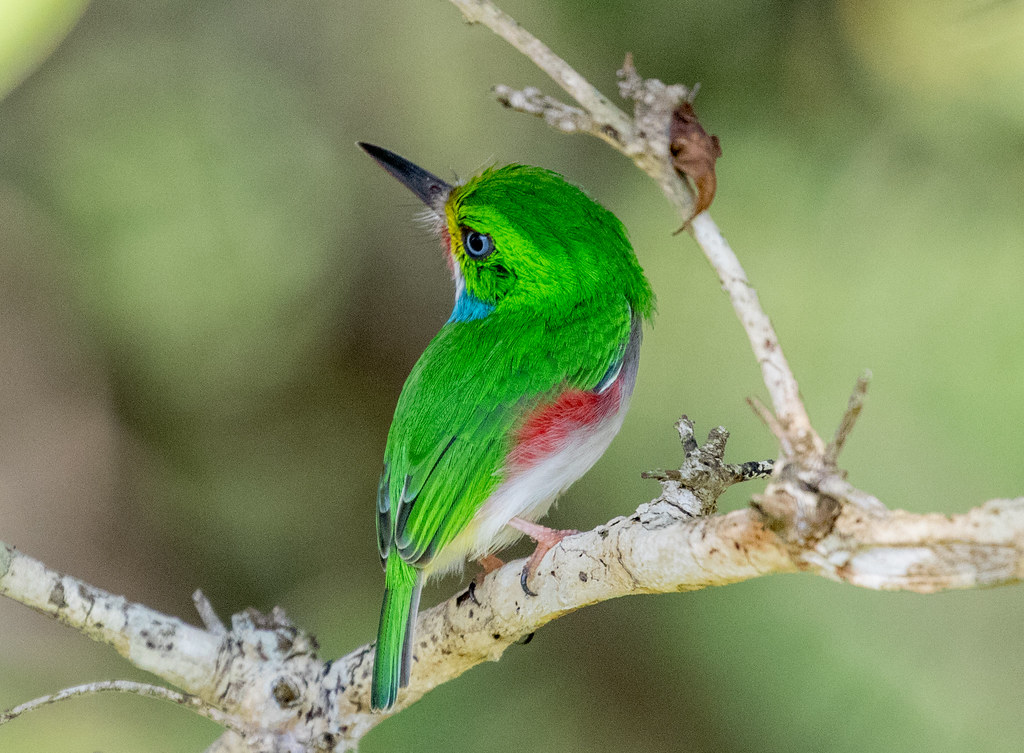

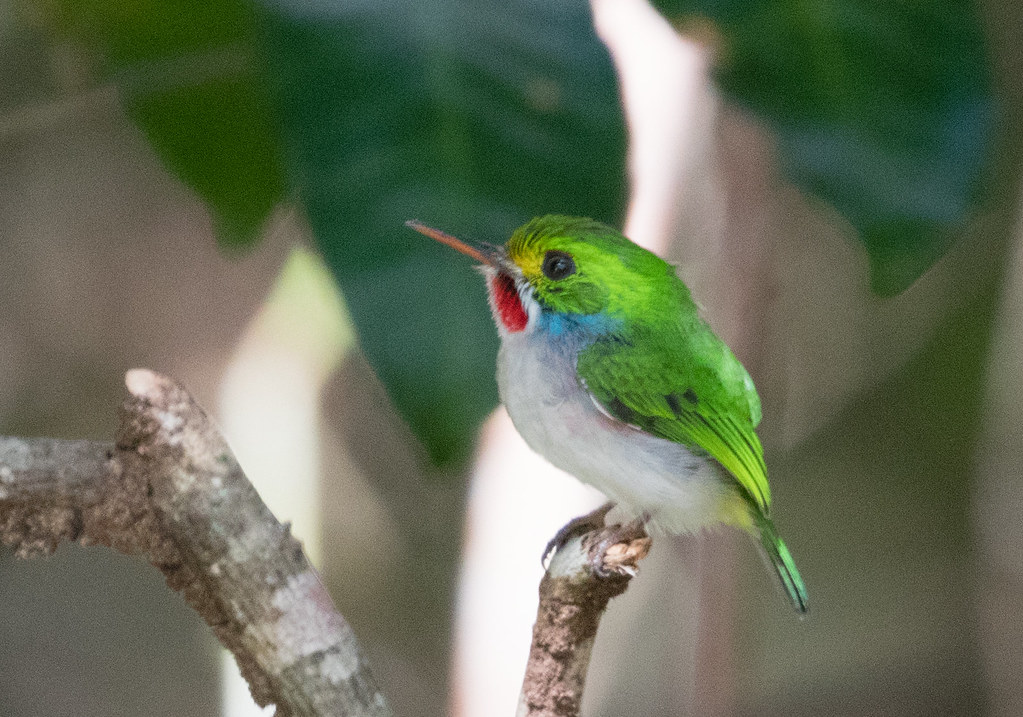

They all have bright green on the crown, back, and tail, a brilliant red throat, and a pale underside. But unlike hummingbirds, these feathers are soft, the colors rich and shiny but not iridescent.

Each of the five todies has a unique combination of pink, baby blue, and/or yellow on the flanks and under-tail—only the Cuban Tody features all three of those colors, so its scientific name is Todus multicolor.

The head is oversized, the tail very narrow and not very long, and the bill is flattened and rounded at the tip, the lower mandible red.

At 4.3 inches in length, the Cuban Tody is 10 percent shorter than our chickadees, but a lot of a chickadee’s length is in its tail, and a lot of a chickadee’s bulk is due to thick body feathers. The tody is all head and body, lives on Cuba where thick insulation is hardly necessary, and again, it’s related to kingfishers, so it’s muscular and rather heavy compared to the chickadee.

I’d never been to the Caribbean until this month, and so my only experiences with todies were reading about them and looking at photos and videos. The real thing was just as spectacular as the photos captured, and even more wonderful because it turns out the Cuban Tody is rather confiding. Our birding group of 13 didn’t faze the little birds at all.

They’re busy little guys, sitting in one spot on a branch, usually just about eye level or even below, for several seconds up to a minute or so. Their feet may stay in the same spot, but even while sitting they’re rather animated, looking this way and that searching for insects. When I got one in focus in my camera, holding the shutter release down I’d capture several different poses within a single second. Todies don’t understand photography but they do understand hunger: feeding fairly constantly from morning until night.

Todies are not flycatchers, and seldom grab an insect in mid-air. According to the British Ornithologists’ Union’s wonderful A Dictionary of Birds, they capture insects and spiders from the undersides of leaves and twigs.

“They sit quietly but alertly on twigs or branches, constantly moving their heads and eyes with rapid and jerky movements, and occasionally flick their wings. Typically the bird perches with its bill pointing upwards (at angles up to 45 º), and scans the lower surfaces of leaves above it.

On spying an insect the tody flies up to the leaf, snaps its bill audibly, and continues in an unbroken arc to another perch.”

Todies excavate long, narrow burrows in banks, and road and trailside cuts, to produce their 2-3 eggs. Both parents incubate, but neither spends more than a quarter of its day incubating, and only in short bursts at a time, so it takes 3 weeks or more for the young to hatch.

Suddenly the parents make up for their inattentiveness by feeding the nestlings at the highest rates recorded for any bird: up to 140 feedings for each chick every day.

If a pair of todies loses their own chicks, they often help their neighbors raise theirs.

James Bond, the ornithologist whose name was appropriated by the birder Ian Fleming for his most famous creation, spent many years in the West Indies. After spending just a week on Cuba, I could appreciate exactly why. As wonderful as I expected the Cuban Tody to be, the anticipation was shadowed by the actual event.

Laura Erickson

Laura Erickson, 2014 recipient of the American Birding Association’s prestigious Roger Tory Peterson Award, has been a scientist, teacher, writer, wildlife rehabilitator, professional blogger, public speaker, photographer, American Robin and Whooping Crane Expert for the popular Journey North educational website, and Science Editor at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. She’s written eight books about birds, including the best-selling Into the Nest: Intimate Views of the Courting, Parenting, and Family Lives of Familiar Birds (co-authored by photographer Marie Read); the National Outdoor Book Award winning Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids; 101 Ways to Help Birds; The Bird Watching Answer Book for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology; and the National Geographic Pocket Guide to Birds of North America. She’s currently a columnist and contributing editor for BirdWatching magazine, and is writing a field guide to the birds of Minnesota for the American Birding Association. Since 1986 she has been producing the long-running “For the Birds” radio program for many public radio stations; the program is podcast on iTunes. She lives in Duluth, Minnesota, with her husband, mother-in-law, licensed education Eastern Screech-Owl Archimedes, two indoor cats, and her little birding dog Pip.

Leave a Reply