As spring turns to summer in the southern hemisphere, the Punta Tombo Natural Protected Area on Argentina‘s central coast comes alive, with the chicks of some 180,000 pairs of nesting Magellanic penguins braying and peeping 24/7.

That penguin-palooza was nearing a crescendo in November 2021 when tragedy struck. A local rancher named Ricardo La Regina, then 33, intentionally drove a backhoe through nesting grounds just north of Punta Tombo, home to the world’s second-largest Magellanic penguin colony and part of the UNESCO’s Patagonia Azul Biosphere Reserve. An estimated 175 nests were crushed and more than 100 penguins killed in what the Argentine press dubbed the “Punta Tombo Penguin Massacre.”

But after a historic court case, some surprising good has come from the disaster, including new legal protections for penguins and a variety of other wildlife.

A crucial sanctuary

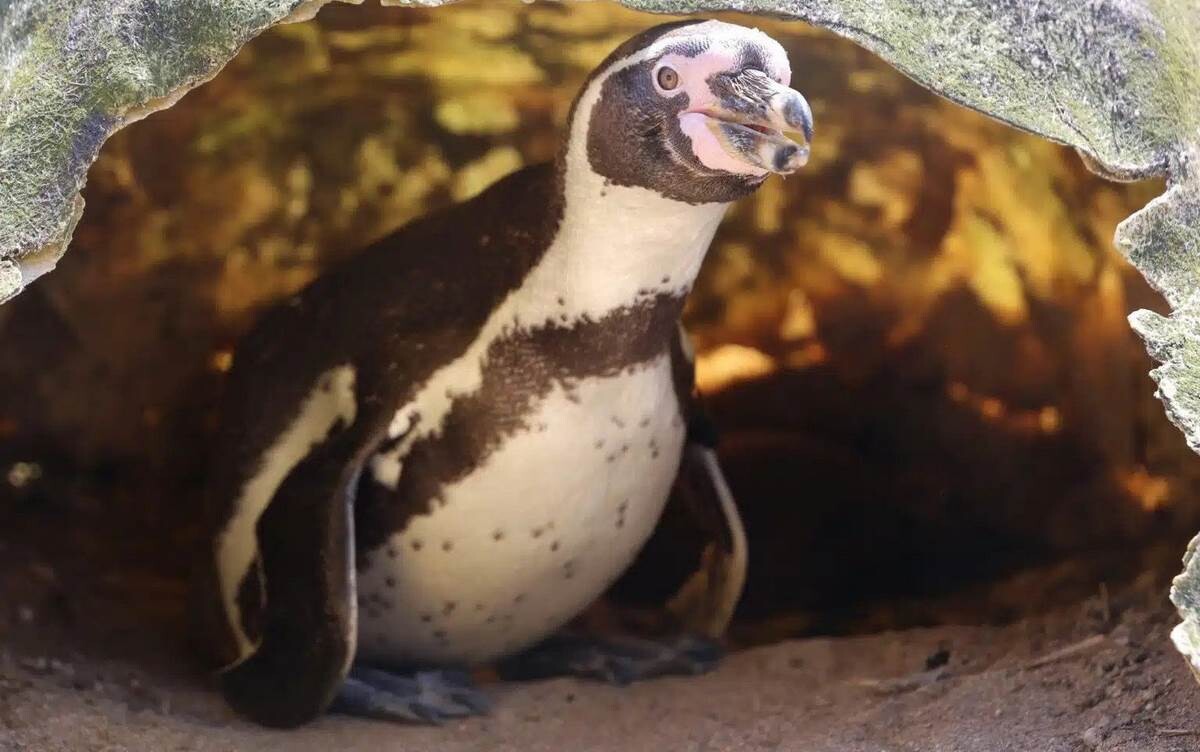

Three times faster than the world’s speediest Olympic swimmer, Magellanic penguins spend most of their lives at sea, seldom coming to shore except to breed and nest along South America’s southern coasts and on its islands. On land, the stout little waddlers build burrows beneath tussocks, tall grasses, and bushes. They’re not currently listed as endangered or threatened, but populations have been declining since the 1980s, likely due to a combination of manmade threats: Oil spills have killed tens of thousands of birds. Development and pollution have wrecked habitat. Overfishing has diminished food sources, as has climate change, which also causes heat waves, submerged nesting sites, and other effects.

The first Magellanic penguins to nest in Punta Tombo settled on the La Regina family ranchlands in the mid-1920s. As the colony grew, the La Reginas wanted to protect the birds, donating 520 acres to create a preserve at Punta Tombo, with an additional 35 acres for an interpretive center that now hosts more than 100,000 visitors a year. Ricardo La Regina’s grandfather and uncle were Punta Tombo’s first park rangers—but his attempt to build a road through the colony in 2021 put a black mark on the family’s history of conservation.

After officials learned of the destruction, the first biologists to assess the damage were Global Penguin Society founder and National Geographic Explorer Pablo “Popi” Borboroglu and Laura M. Reyes, the group’s conservation director, who is married to Borboroglu. They found 22,000 square feet of scarred landscape. Underground burrows were exposed, the bushes that had shaded them plowed into a pile. “It was a nightmare,” Borboroglu says. “I never thought I was going to see something like that in my life.”

Penguins get their day in court

Borboroglu and Reyes documented the carnage, making videos and photos of dead chicks and other evidence. In the weeks that followed, they calculated the approximate population and nesting density of the damaged area, then submitted a detailed report to the government. Because wildlife crimes in Argentina have historically been brushed aside, the biologists thought the odds of the case ever going to court were slim.

But news of the Punta Tombo massacre was widely reported, and last November, Borboroglu was among the expert witnesses called to testify against La Regina. In his defense, the rancher argued that the protected area prevented him from grazing cattle. He was frustrated, he said, because the government had ignored for a decade his petition to create a road and clarify boundaries between his ranchlands and the reserve. Borboroglu presented his photos and described how he’d seen tracks where the backhoe had rolled over the roof of a burrow, collapsing it.

The court found La Regina guilty of environmental damage, animal cruelty, and malice.

He was sentenced to a suspended three-year jail term, meaning La Regina likely won’t serve time unless he violates his parole. But he also faces up to a half-million dollars in fines and tightened restrictions on how he can manage his land, keeping his cows away from penguins and their burrows.

“This was a historic achievement, Argentina’s first-ever environmental case to reach an oral trial and a groundbreaking victory for penguins and conservation,” says Borboroglu, who has since been named one of the 2025 Rolex National Geographic Explorers of the Year. The case, he says, “sets a crucial precedent for environmental justice and strengthens protections for wildlife and their habitats in Argentina.”

As a result of the trial, the Argentine government has taken steps to expand the protected area around Punta Tombo eightfold, from roughly 500 acres to nearly 4,000, and has called for a new management plan to preserve penguins and other imperiled seabirds, plants, and sea lions along the coast. The government is also considering a proposal to include environmental crimes in the national penal code, and in Patagonia, a newly established environmental prosecutor’s office will specialize in wildlife crime.

“This precedent-setting case is becoming a force for change,” says José Ma Musmeci, president of Fundación Patagonia Natural, one of several nonprofit conservation organizations to join the government’s case against La Regina.

The government’s actions are an important move forward, says American seabird biologist and National Geographic Explorer Dee Boersma, of the University of Washington, who has spent 43 years studying Punta Tombo’s Magellanic penguins. Also critical, she stresses: protecting the marine environment, where penguins spend three quarters of their lives, particularly as Argentina is in the midst of an oil boom, putting penguins at risk of spills. “Having a place to breed is a good first step,” Boersma says, “but they also need a place to feed.”

Meanwhile, penguins have returned each year to Punta Tumbo, although not to the damaged area of the nesting grounds, which will take years to recover. New chicks have fledged. By this time of year, most have left, surfing ocean currents north to more tropical latitudes.

This article by Rene Ebersole was first published by National Geographic on 10 April 2025. Lead Image: Magellanic penguins have a stretch of white feathers that swoops down from each eye, joining to form a strap around the neck. Photograph By Diego Cabanas.

What you can do

Wildlife continues to face threats, which include hunting, poaching, illegal trade in animal products, habitat loss as well as a rapidly changing climate.

Become a Wildlife Champion by supporting our conservation partners with a monthly donation as little as $1.

Donate

Donate

Leave a Reply