Steve Mills is an award-winning photographer. His image ‘The assassin’ won the Birds: Behaviour category in the prestigious Veolia Environment Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2011. He was the only category winner from Britain.

Your photograph, “The assassin”, won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2011, Behaviour: Birds category last year. What draws you to birds as a subject in particular?

For me, all wildlife is wonderful but birds are simply fantastic. For one thing they are so accessible. Close encounters with other wild animals are few and far between. They tend to be secretive creatures of the night, reluctant to be seen. It’s birds that allow us that connection with the natural world. We see them everywhere – in the garden, in the park, above the city etc. My fascination has always been more than simply ‘What bird is that?’ but rather ‘What is it doing?’ and ‘Why is it doing it?’ and I think this lifelong interest in bird behaviour has helped me enormously in my photography.

Could you reveal a bit about the photo and the process of getting the shot?

Following a week of snow cover and sub-zero temperatures in the north-east of England many birds were struggling. Snipe and woodcock, amongst others, had been forced to the coast in the search for unfrozen feeding areas. Most had abandoned any pretence of secrecy and were probing anywhere there was even the tiniest patch of grass sticking up through the snow.

I drove around the lanes near my home looking for a likely spot and came across a tiny patch of exposed grass that would allow me to use the car as a hide with the sun well-positioned. With my 500 lens balanced on the window I settled down to wait. Eventually a snipe appeared and began frantically feeding only a few metres away. This was what I’d hoped for and felt my preparation had been suitably rewarded. What happened next was where the luck came in. As with all good wildlife photography there’s preparation, understanding the behaviour of your subject, some decent kit etc., but overriding all this is whether you get lucky.

The snipe, desperately hungry, showed little regard for its exposed position and within seconds had paid the ultimate price. As I watched the snipe through the camera my left eye caught a movement. A merlin arrived at speed inches above the snow, and hit the snipe talons first. The ensuing struggle lasted only a matter of seconds. After looking up, seemingly straight at me, the merlin gave a series of rapid and violent pecks to the head of the snipe to end the uneven contest. Of the 15 shots I was able to take this image worked best.

Have you any tips for aspiring wildlife photographers?

You’ve got to be passionate because it can be frustrating. There isn’t an album in the world big enough for all the ‘almost’ photos – those missed through not quite being in the right place, not reacting quickly enough or having crucially misjudged a setting. That happens to everyone and all you can do is to try to learn from these experiences to make you more likely to get the shot next time.

Wildlife, including birds, tends to be timid, so a long lens helps enormously but if you get to know how your subject behaves you can often predict what it will do and position yourself accordingly. For example, large birds always take off into the wind so by positioning yourself well you’ve got more chance of a bird flying towards you initially. Getting to know your subject also increases your chances of getting action shots such as a bird feeding, preening, wing-stretching, interacting with others etc. This type of action can often add punch to a photo.

Whatever camera you’re using, I recommend you make sure you’re completely comfortable with its settings. Make sure you can change them without losing vital moments having to fiddle about trying to find this or that button. Understanding your camera is vital because, in wildlife photography, you often don’t get a second chance.

Use the light to your advantage. If there is bright sunlight try shooting early in the morning or just before dusk when the shadows are less harsh and the bird is lit from a lower angle.

For birds, keep your shutter speed high. This is particularly important for moving or flying birds. To do this you may have to sacrifice depth of field or ISO.

Finally, never think that you have to travel across the country or even further afield to get great shots. My wife and I run a conservation organisation in Greece – Birdwing – and this takes me to spectacular birdwatching sites where I spend days at a time behind a camera, usually in wonderful light. Ironically however, this picture was taken only yards from my house in the north-east of England, which demonstrates something I’ve learned time and again – in wildlife photography you never know what is around the corner and that extra hour in the field can sometimes be richly rewarded.

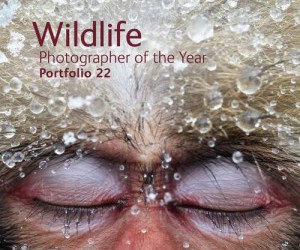

Pre-order now and save 20% when you buy the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Portfolio 22 book:

|

Wildlife Photographer of the Year winning inspirations, part one: Steve Mills on “The assassin” was written by Katherine and published in the Hoopoe, a Blog by NHBS.

Leave a Reply