It’s 3.40pm on a Thursday and Penguin 999.000000007425712 has just returned to the Stony Point penguin colony in Betty’s Bay, South Africa, after a day of foraging. She glides elegantly through the turquoise waters before clambering comically up the rocks towards the nest where her partner is incubating two beige eggs. She doesn’t realise it, but a rudimentary knee-high fence has funnelled her towards a state-of-the-art weighbridge. When she left the colony at 6.45am this morning she weighed 2.7kg. Now, after a full day of hunting, she has gained only 285g.

Eleanor Weideman, a coastal seabird project manager for BirdLife South Africa, is concerned. “In a good year they come back with their stomachs bulging,” she says. Penguins can put on up to one-third of their body weight in a single day of foraging. “But there’s just no fish out there any more.”

Tomorrow, Penguin 999.000000007425712 and her partner will swap roles: she will stay on the nest and he will go out to forage for food. If all goes well, they will be able to raise two clutches of two eggs this season. But at the current rate they may have to abandon this nest and give up on breeding for the year.

The number of African penguins has declined by more than 99% in the past 120 years. At the current rate of decline (7.9% per year), the species – African’s only penguin – will be extinct in the wild by 2035.

Not only would this be an ecological disaster – penguins are an indicator species for the entire ecosystem – but it would also be devastating for the South African tourism industry. A 2018 study on the colony at Boulders Beach in Cape Town showed that it contributes 311m rand (£13m) a year to the local economy.

Now, in an unprecedented attempt to stop this from happening, two NGOs – BirdLife South Africa and Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds – have taken South Africa’s minister of forestry, fisheries and the environment, Barbara Creecy, to court claiming she has failed to implement “biologically meaningful closures” to fishing around six penguin colonies which are home to 76% of the global African penguin population.

The decision to petition the courts came after the minister chose not to follow some of the key recommendations made by an international review panel she appointed.

Alistair McInnes, who heads up the Seabird Conservation Programme at BirdLife South Africa and is the author of the founding affidavit in the court papers, says that the desired fishing bans would apply only to commercial vessels using purse-seine nets to target small pelagic [open seas] species such as sardines and anchovies. Purse-seine nets are like giant drawstring bags that target entire shoals. African penguins are specialist feeders and predominantly eat these species – and South Africa’s sardine and anchovy stocks are at all-time lows.

Penguins are not the only ones who stand to benefit from such a ban. Cape cormorants (another endangered bird species) also feed predominantly on small pelagic fish. And small-scale handline fishers have welcomed the proposals, as many of the species they target feed on sardines and anchovies.

The panel of experts appointed by Creecy delivered a report in July 2023, stating that targeted fishing closures around penguin colonies “would be likely to benefit penguin conservation”.

While the minister took some of the report’s recommendations on board, she stuck with existing, but more limited, closures.

In the Stony Point colony, for example, the area closed to purse-seine fishing is three times smaller than it would be if the expert panel’s recommendations were followed – so it’s little wonder that Penguin 999.000000007425712 is having a hard time finding food. And it’s a similar situation in three other colonies where 50% or less of the penguins’ core foraging area is protected under existing rules.

The potential impact of extended fishing closures on the purse-seine industry is hard to quantify, but the body representing fishers says the court action is misguided. “Contrary to environmental NGOs’ statements in the media that the main driver is the purse-seine fishing industry, the impact of fishing [on penguin numbers] is small,” the South African pelagic fishing industry association said in an email to the Guardian. It said the “environmental NGOs” had delayed a “process that is tasked with establishing what are the main drivers causing the decline in penguin numbers”.

Creecy’s office did not respond to requests for comment and the “record of decision”, which the state attorney representing the minister filed in April gave little insight into why she followed some of the panel’s recommendations and did not apply others.

Fishing is not the only driver of population declines. “African penguins are probably the most studied seabird in Africa,” says McInnes. “Loads of research has been done into various threats to their survival.”

These include the climate crisis (extreme heat and heavy rain can both prove disastrous during nesting season); land predators (leopards, caracals and honey badgers have all broken into colonies); and the localised threat of noise pollution from “bunkering” (a ship-to-ship refuelling process) at the St Croix colony near Gqeberha.

Nevertheless, prey availability is an important determining factor for the survival of any specialist predatory species, McInnes says, not to mention their ability to reproduce. It is perhaps telling that the only penguin colony in South Africa with a relatively stable population – Boulders near Cape Town – is in an area where purse-seine fishing has been banned for decades.

As McInnes, who has been studying the African penguin for more than a decade, says: “I haven’t met a penguin scientist who doesn’t believe that carefully demarcated closures are part of the solution.”

All Penguin 999.000000007425712 wants to know is where her next meal will come from.

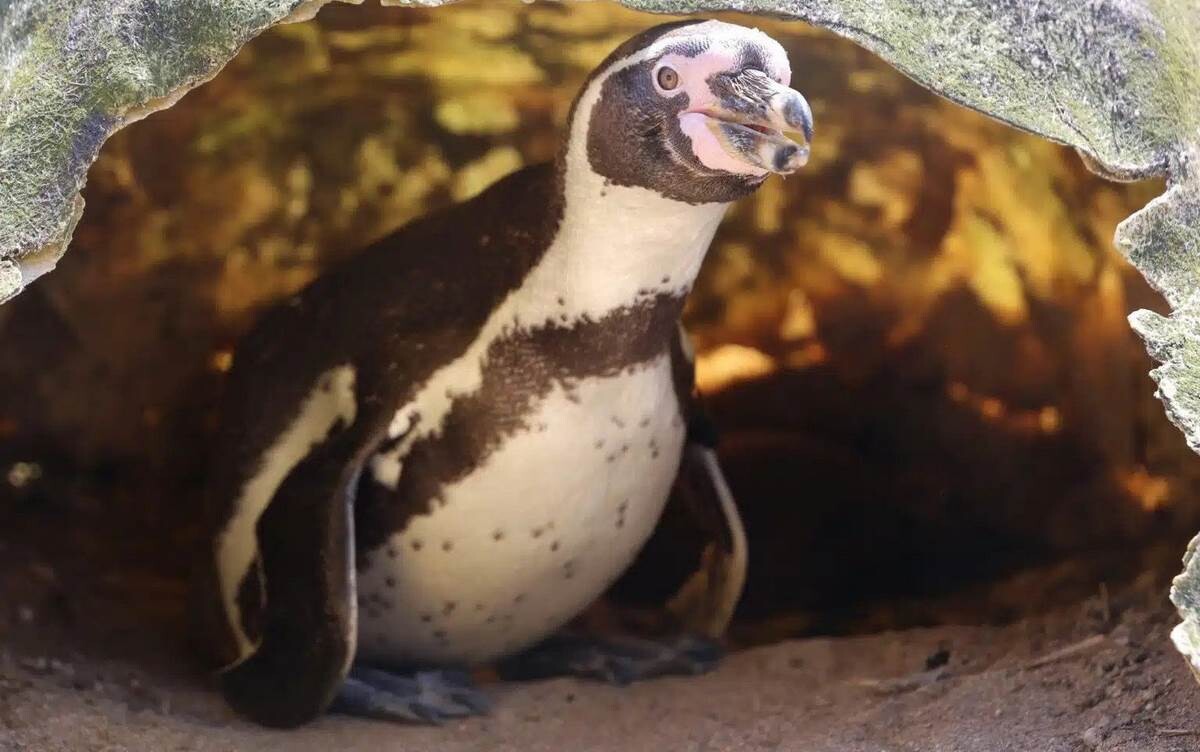

This article by Nick Dall was first published by The Guardian on 23 May 2024. Lead Image: The number of African penguins has declined by more than 99% in the past 120 years. Photograph: Imagebroker/Alamy.

What you can do

Help to save wildlife by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute.

Leave a Reply