It is early spring in 2012 and I am watching an iconic lone male Golden Eagle performing spectacular sky diving displays in the valley of Riggingdale in the stunning remote location of Haweswater. The huge raptor can be seen patrolling his resident territory along with Red Deer grazing the hillsides and the first Meadow Pipits, Lapwing and Skylarks taking up their early breeding grounds, the area is teaming with life. It is peace and tranquility with the only sounds heard are gronking Ravens overhead and the odd screaming of a nearby Peregrine. With nothing but wilderness all around me I feel like I am the only person in the whole national park. Haweswater is surrounded by dramatic mountains and glacially gouged valleys and is regarded as one of the most picturesque locations in Lakeland. The neighboring valley of Mardaleoccupiedresidents less than a hundred years ago before a dramatic change in fortunes had a huge impact on all the surrounding area…

The year was 1919 and the sad news reaches the people of Mardale Green, they awoke to learn that the Manchester Water Corporation had just secured the long awaited Haweswater Act, a compulsory purchase agreement of the day, which granted them permission to build a dam and drown one of Lakelands jewels in its crown. The act read that farmers must abandon their homes along with hundreds of acres of land. Once the dam was built in place the waters will rise to cover the houses, schools and church in the valley to provide added water supplies to the ever growing empires of the north west of England.

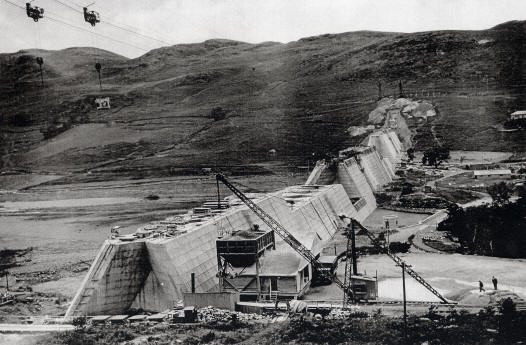

Ten years later in 1929 and work starts on building the large dam construction to the north end of the valley of Mardale. Today there are very few Mardalians, or any of the children remember the flooding back in the 30s. Mr John Henry and his sister Majorie remember it better than most for their father owned and farmed Chappel Hill before the flooding. The time for them to move loomed ever closer so the whole family decided to up sticks and move to their grandfathers farm in neighboring Wet Sleddale. After comfortably settling in at their new home they later heard that included in the area of 110,000 acres bought from Lord Lonsdale for £130,000 was Wet Sleddale. A double blow as they would all have to relocate again to make way for a second dam to be built to provide Mardale with a backup water supply if needed.

During this time a local Mardalian farmer went missing without a trace. The story told by a relative tells how William Martindale, a well to do family man with an affectionate wife and four children mounted his horse and simply rode away one morning. His steed was found in a stable at Kendal a few days later but no other evidence could be found of Williams disappearance as he was never seen again.

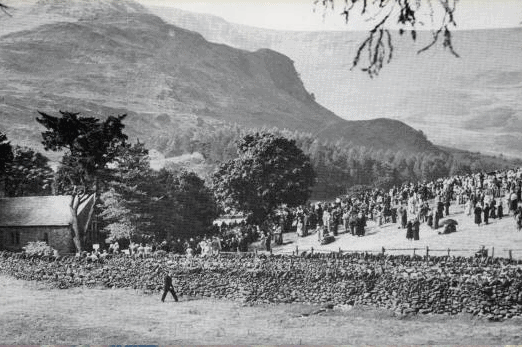

The Mardale people watched on through the next couple of years as work on the dam continued and started to take shape as the locals were supposed to try and get on with their lives. Work was halted in 1931 because of the great depression for four years although I am sure there was some sense of hope for the local communities until work started again. The last farewell for the Mardale residents was on the 18th August 1935 and a service took place at the Holy Trinity church with 75 people present inside the building and over a thousand people gathered on the hillside outside listening to the moving service via loud hailers fastened to the church tower by a local radio expert from Penrith. Brickwork from the church and other major buildings was later used to contribute to the completion of the dam construction as water levels rose and covered all evidence of inhabited communities in 1940.

The building of the dam raised the water levels by 29 meters and created a reservoir 4 miles long and half a mile wide. The dam wall measures 470 meters long and 27.5 meters high and at the time of construction it was considered to be cutting edge technology as it was the first hollow buttress dam in the world. An estimated 140,000 cubic yards of concrete, requiring 190,000 tons of stone and 30,000 tons of cement were used during the dam’s construction. An estimated capacity of 75 million gallons a day are used to supply Manchester. When the reservoir is full it holds 82 billion liters of water which is enough to give every person on the planet 3 baths!

In 1969 with the reservoir in place and covering any evidence of the past residents in the area a pair of Golden Eagles moved in and took up territory in the neighboring valley of Riggingdale. These iconic birds are prone to any form of disturbance and need a vast remote wilderness area to survive in. Golden Eagles are very elusive and secretive as it was proved when a pair nested in the Wastwater area in the 1970s for 7 years without being made aware by the public. The RSPB provided a hide and view point looking into the valley of Riggingdale to give visitors the opportunity to admire these majestic birds and learn about them. The Eagles holding aterritoryat Riggingdale produced 16 chicks since the first birds took up residence in the valley. Most of the fledged birds would move off into the Pennines and over grouse moors where they would never be seen again.The latest pair lasted until 2004 when the female disappeared without a trace just like local Mardalian family man William Martindale didnearlya hundred years previous. In the last few decades when an eagle from the pair did go missing at Riggingdale a replacement moved in straight away to take up the territory as there were nearby pairs in Wastwater, Kielder and the Borders producing young birds through the years looking to take up breeding attempts, but by 2004 the surrounding pairs had decreased and there wasn’t any suitable birds around ready to take up the vacancy which has not been filled since. Another eagle did turn up in the valley in 2010 which must have gave the lone male hope, but when they came to interact it turned out to be a White-Tailed Eagle which had ventured south from Scotland. It was the same false hope the Mardalians got when work was halted on the dam construction before starting again a few years later leading to completion.

Back to the present day and the lone male Eagle can still be seen displaying at the head of the valley over the famous old Roman road of High Street. The road was built to connect the forts at Brocavum near Penrith and Ambleside. The high street range had quite gentle slopes and a flat summit which encouraged the Romans to build the road on the higher ground rather than through the valleys which were densely wooded and marshy during that time making them susceptible to ambushes. The Roman Empire used an eagle as their emblem as the bird represented strength, courage,far-sightedness, immortality and was a symbol of the power of the Roman Legion. The birds were considered to be the kings of the air and the messenger of the highest gods. You could say that the lone eagle is one of the last living representations of the dominant reign of the Roman Empire in England.

There is new hope for the future of the lone eagle at Haweswater as the RSPB has just taken over tenancy of two farms of 7200 acres of the total of 26,000 acres owned by the United Utilities. The change in management was undertaken because the water company had concerns of the water quality deteriorating, and the right management of the upland areas will provide cleaner water supplies. Over 7 million pounds was spent improving filtration at a small water treatment plant at Castle Carrock reservoir a few years ago, so add a few extra zeros to the figure for Haweswater reservoir which provides over 75 million gallons of treated water a day to millions of people. The necessary management will mean taking grazing pressure off to promote natural growth, and new tree plantations to stop the erosion of soil into the reservoir. This will provide a healthy balance to thebiodiversity of species in the long term, encouraging a range of habitatsand giving more food source options to opportunist Eagles. ‘Goldies’ are regarded as the most successful predators on the planet as over 200 species of mammal and bird have been recorded on their prey list around the world. A large part of Golden Eagles diets in Britain is Sheep and Deer carrion. The condition of upland areas dictate our water quality and it just shows that upland land management is far more important for the majority of people and their health along with potentially saving £millions, not just for a small minority that want to shoot Red Grouse for a hobby.

So what does the future hold for England’s Golden Eagles? Will their hopes be washed away like those Mardalian residents nearly a century ago…or will the birds show their true strength, courage and immortality with the return of an Eagle Empire…

Ewan Miles

www.wildlifewarrior02.blogspot.com

references –

http://raptorpolitics.org.uk/2012/04/14/a-new-home-for-hen-harriers/

http://www.bible-history.com/archaeology/rome/2-roman-eagle-bb.html

http://www.mardale.green.talktalk.net/

http://www.rspb.org.uk/reserves/guide/h/haweswater/

Ewan Miles

Ewan Miles is currently working on the isle of Mull for Sea Life Surveys as a wildlife guide. As well as trying to inspire passengers about the wildlife off the north coast of the island he also contributes to the research of the marine life. His local stomping ground is the vast upland area of Geltsdale, Cumbria in the Northern Pennines.

Leave a Reply