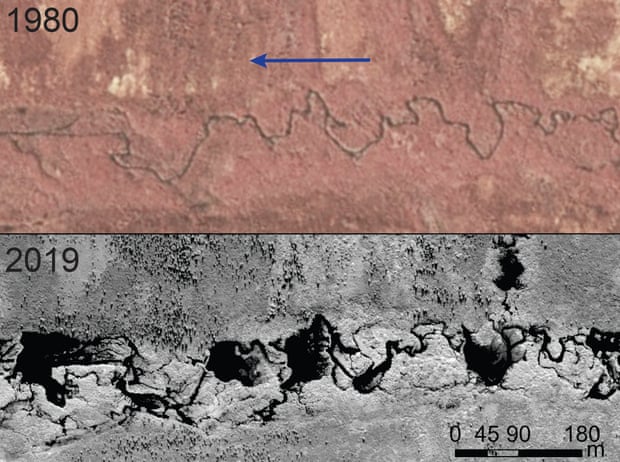

The stream through western Alaska never looked like this before. In aerial photography from the 1980s, it wove cleanly through the tundra, thin as thread. Today, in satellite images, it appears as a string of black patches: one large pond after another, dozens of metres apart.

It’s a transformation that is happening across the Arctic, the result of landscape engineering on an impressive scale. But this is no human endeavour to reshape the world. It is the work of the North American beaver, and there is no sign of it stopping.

Were the waddling rodents making minor inroads, researchers may never have noticed. But the animals are pouring in, pushing north into new territories. The total number of animals is far from clear, but the ponds they create are hard to miss: in the Arctic tundra of Alaska alone, the number of beaver ponds on streams have doubled to at least 12,000 in the past 20 years. More lodges are dotted along lakes and river banks.

“What’s happening here is happening on a huge scale,” says Ken Tape, an ecologist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, who is tracking the influx of beavers into the sparse northern landscape. “Our modelling work, which is in progress right now, shows that this entire area, the north slope of Alaska, will be colonised by beavers by 2100.”

The preponderance of beavers, which can weigh as much as 45kg, follows a collapse in trapping and the warming of a landscape that once proved too bleak for occupation. Global heating has driven the shrubification of the Arctic tundra; the harsh winter is shorter, and there is more free-running water in the coldest months. Instead of felling trees for their dams, the beavers construct them from surrounding shrubs, creating deep ponds in which to build their lodges.

The new arrivals cause plenty of disruption. For some communities, the rivers and streams are the roads of the landscape, and the dams make effective roadblocks. As the structures multiply, more land is flooded and there can be less fresh water for drinking downstream. But there are other, less visible effects too. The animals are participants in a feedback loop: climate change opens the landscape to beavers, whose ponds drive further warming, which attracts even more paddle-tailed comrades.

Physics suggested this would happen. Beaver ponds are new bodies of water that cover bare permafrost. Because the water is warm – relatively speaking – it thaws the hard ground, which duly releases methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases.

Scientists now have evidence this is happening. Armed with high-resolution satellite imagery, Tape and his colleagues located beaver ponds in the lower Noatak River basin area of north-western Alaska. They then analysed infrared images captured by Nasa planes flying over the region. Overlaying the two revealed a clear link between beaver ponds and methane hotspots that extended for tens of metres around the ponds.

“The transformation of these streams is a positive feedback that is accelerating the effects of climate change, and that is what’s concerning,” says Tape. “They are accelerating it at every one of these points.”

Because the Nasa images give only a snapshot in time, the researchers will head out next year to measure methane on the ground. With more measurements, they hope to understand how the emissions vary with the age of beaver ponds: do ponds release a steady flow of methane, or does the release wane after a decade or two?

Alaska is not the only region scientists are watching. Beavers are on the move in northern Canada too, where the creation of ponds over permafrost will have a similar effect. “The scale of the issue in terms of space and numbers is huge,” Tape says.

Helen Wheeler, an associate professor at Anglia Ruskin University, works with communities in the Gwich’in settlement area of northern Canada. There, the beaver population appears to be rising more gradually than in Alaska, but surveys conducted with boats and drones still point to a doubling since the 1960s. “We do see an increase in beavers, but it’s not the exponential rise seen in some areas of Alaska,” Wheeler says. “There’s a lot of variability year on year, which probably reflects what a harsh environment it is.”

The beavers do not have a wholly negative impact. The mini-oases created by the animals can boost local biodiversity. And for some communities, the animals themselves are a potential source of meat and perhaps even fur.

Still, many are wary. While not all beavers build dams, those that do can affect water quality and the movement of fish, and make places inaccessible by flooding the land and blocking the routes through it. Even without methane emissions to worry about, researchers and indigenous communities are wondering what, if anything, should be done.

The question will be up for discussion in February when researchers, indigenous groups, land managers and others in the Arctic Beaver Observation Network hold their annual meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska. The meeting will draw on experts who manage beavers in other regions to explore the possible options.

“If it’s a problem, what can we do about it? I have no answers,” Tape says. “You can put a bounty out there and start killing them, but the moment you stop, three to five years later you are going to be back in the exact same position. Not to mention the fact that it’s logistically impossible to do that.”

“People do eat them, but I would say less now than they used to,” Tape adds. “I’ve never had it, but I think that is going to change. I hear it’s good eating.”

This article by Ian Sample was first published by The Guardian on 2 January 2024. Lead Image: Beavers in the area studied by the University of Alaska in the north-west of the state. Photograph: Ken Tape/University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

What you can do

Help to save wildlife by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute.

Leave a Reply