Donald Trump has called big-game trophy hunting a “horror show”, despite his own sons’ participation in elephant and leopard hunts, and in 2017 he formed an advisory board to steer US policy on the issue.

But rather than conservation scientists and wildlife advocates, it is composed of advocates for the hunting of elephants, giraffes and other threatened, charismatic species. And observers say that since Trump took office, court rulings and administrative decisions have in fact made it easier for hunters to import the body parts of lions, elephants and other animals killed in Africa.

Members of Trump’s advisory board, called the International Wildlife Conservation Council (IWCC), argue that the sport, in which wealthy hunters pay tens of thousands of dollars to shoot endangered megafauna, is a laudable method of conservation abroad.

“This council will be focused on making hunting a better tool for conservation,” said John Jackson III, a member of the IWCC and founder of Conservation Force, an international hunting non-profit. Only two of the council’s 16 members are not active advocates for trophy hunting – the rest belong to groups such as Safari Club International and the National Rifle Association. Instead of discussing whether the sport should be limited, the group is focusing on how to broaden its reach.

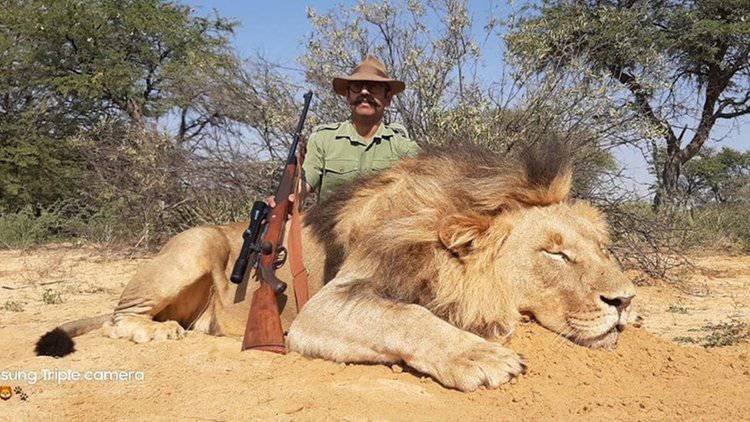

Awareness of trophy hunting has increased thanks to social media. In 2015, a Minnesota dentist ignited debate when he shot Cecil, an enormous, black-maned lion immensely popular with camera-wielding tourists and a focus of research. More recently, a Kentucky woman has been criticized for triumphantly posing next to a giraffe she killed; conservationists estimate giraffe populations have fallen 40% since 1990.

Trophy hunters hold immense clout in the Trump administration. The president’s sons, Donald Jr and Eric, frequently hunt in Africa. And the hunting advisory council operates under the auspices of the interior secretary, Ryan Zinke, who received $10,000 from the Safari Club during his 2016 congressional campaign. The lopsided composition of the council has critics worried its decisions will protect their chosen pastime, not the animals.

“People who consider themselves conservationists don’t consider trophy hunting conservation,” said Tanya Sanerib, international legal director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “It’s an elite, bourgeois activity.”

The US cannot ban its residents from hunting in another nation, but it does regulate the importation of trophies – the body parts of animals killed abroad. Hunters seeking to import the remains of species protected under the Endangered Species Act must provide proof that killing an individual animal broadly enhances the species’ odds of survival.

In 2017, Trump’s interior department eased Obama-era restrictions on trophy hunting, and the president used Twitter to voice displeasure with the practice, writing it was unlikely he would “change my mind that this horror show in any way helps conservation of Elephants or any other animal”. The department then reinstated the ban, but a subsequent court ruling found that it was not based on proper rule-making procedures, and imports continue.

Irrespective of Trump’s comments, the Fish and Wildlife Agency, which oversees trophy imports, holds that well-regulated sport hunting is beneficial to the survival of endangered species. “Most wildlife would cease to exist if it wasn’t for the habitat and the anti-poaching activity” funded by trophy hunters, said Jackson of the IWCC.

The wealthy Americans who hunt abroad say their very presence deters poachers, and their fees keep habitat from being converted to other uses. If a field’s purpose is switched from hunting to cattle grazing, a lion is less a revenue engine than something that might eat one’s livelihood.

Sport hunting’s contribution to species preservation is far from clearcut, however. Researchers tend to agree that a robust hunting industry successfully prevents native grassland from being converted to agriculture, and that it generates important revenue for communities without a viable ecotourism industry. But meeting the bar for imports – by proving that hunting improves a species’ chance of survival – is much more complex. “It has to be a net positive for conservation,” said Scott Creel, a conservation biologist at Montana State University, “and that’s where there is some debate.”

There’s evidence that sport hunters weed out desirable genetic traits by killing the largest and strongest animals. Some researchers say well-regulated trophy hunting promotes biodiversity; others contend it only protects the species hunters want to shoot. And claims that legal hunters deter poachers may be spurious – researchers have found that ending the legal trade of ivory is the best way to go.

Creel’s own research into Zambia’s lion population showed that trophy hunting policy can have a widespread effect on the health of a species. “Our data showed that [lions] appeared to be overhunted,” he said. “The Zambian government implemented a three-year trophy hunting ban, and we immediately saw a response – the population shifted from declining to growing, male survival improved, and more cubs were being raised.”

As evidenced by the controversy surrounding recent high-profile kills, sport hunting poses an ethical conundrum as well. Sanerib sees the activity as a “pay-to-play” system that counters the Endangered Species Act’s intent. “As long as you have enough money, and you allegedly are putting it toward the conservation of the species, you can do whatever you want,” she said.

Jackson, the IWCC member, sees it another way. Politicians and the mainstream media have “put out bad information, and people have no idea that they’re attacking a paradigm that saves more wildlife than anybody, and to which there is no alternative,” he says. “I’ll repeat that – no alternative. When the hunting community is disenfranchised, that’s the end of most of the habitat, and most of the wildlife.”

Jackson’s hunts over the years may have resulted in the death of more than a dozen bull elephants – but he believes his cash has saved hundreds of others.

This article was first published by The Guardian on 17 Jul 2018.

We invite you to share your opinion whether you agree with Trump that trophy hunting is good for wildlife? Please vote and leave your comments at the bottom of this page.

Thank you for voting.

Editorial Comment: The purpose of this poll is to highlight important wildlife conservation issues and to encourage discussion on ways to stop wildlife crime. By leaving a comment and sharing this post you can help to raise awareness. Thank you for your support.

Leave a Reply