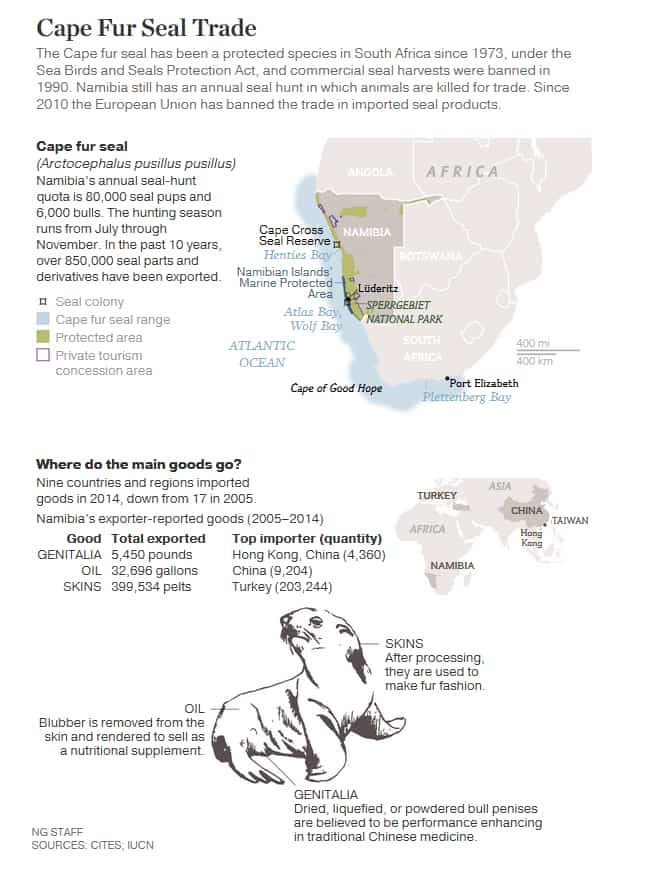

Namibian Sunshine isn’t what you might think. It’s oil derived from the blubber of the Cape fur seal, advertised online as rich in Omega-3 fatty acids and allegedly more readily absorbed by the human body—given its mammalian source—than fish oil.

Since 2005 Namibia has exported almost 33,000 gallons of sunshine, nearly a third to China.

But export of seal pelts dwarfs Namibia’s seal oil business—400,000 of them during the past decade—representing one of the largest trades of any mammal out of Africa.

Most go to Turkey, where fashion mogul Hatem Yavuz has them made into “wild fur” coats. According to Seven Network, one of Australia’s main free-to-air commercial television networks, Yavuz controls 60 percent of the global market in seal products.

“I come from a family of furriers,” Yavuz said in a Whatsapp phone call from his home in Istanbul. “Lamb’s wool is the Toyota of the market, mink is the Mercedes, and the sables, chinchillas, and seals are the Bentleys.” He says it takes seven pelts to make a man’s seal coat, which can sell for between $3,000 and $30,000. “China and Russia enjoy this ‘bling bling’—they’re my main customers. You won’t see Turks wearing the Bentleys: We’re good at producing but not at wearing.”

Greece, like Turkey, was recently an importer of seal skins from Namibia. But in 2010 the EU banned imports of seal-derived products in response to public outrage over the way seal pups are clubbed to death, or “harvested” in scientific speak. (The EU ban exempts indigenous Inuit in Greenland and the Canadian territory of Nunavut.)

“Global markets for seal products are closing fast,” says the Humane Society International. More than 35 countries have now banned products of commercial seal hunts, including the United States, the EU, and Taiwan. (In 1972 the United States Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibited the hunting, killing, capture, and harassment of seals and other marine mammals.)

Namibia, Canada, and Greenland are the last places where seals are harvested commercially. Canada’s is the world’s largest marine mammal hunt, with some 350,000 harp seals taken each year. Namibia, where seals are listed among the most important commercial marine species, has set an annual hunt quota of 80,000 Cape fur seal pups and 6,000 bulls.

Export of seal pelts represents one of the largest trades of any mammal species out of Africa.

The story of sealing in Namibia focuses sharply divergent interests: an overseas mogul who wants to expand his trading empire; animal welfare advocates who want to end seal hunts; biologists who worry about the long-term survival of the species; fishermen who blame the seals for stealing their catch; and a government agency, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, that controls the seal trade and seems intent on keeping it going in the face of a global trend to close it down.

Cape fur seals are found in the waters off southwestern southern Africa and are estimated to number approximately 1.7 million. More than half are in Namibia, and the rest in South Africa—which banned commercial seal harvests in 1990—and Angola. The seals aren’t threatened with extinction, but under the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the 183-nation body that regulates international wildlife trade, they’re listed as a species that may become threatened if their trade isn’t closely monitored and controlled.

Moreover, “If CITES is serious about improving animal welfare standards in trade, then it really should raise the issue of the Namibian seal hunt,” says Pat Dickens, the force behind Seals of Nam, a Namibian nonprofit founded in 2010 with the goal of ending the country’s sealing industry. Ahead of the CITES wildlife trade conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, next week, Dickens initiated an online petition calling for the Cape fur seal trade to be blacklisted because of the inhumane ways seals are killed, the harm harvests do to seal populations, and lack of transparency in the sealing business.

While the seal pups’ soft skins are used for coats—his Bentleys—the bulls are killed for their penises, or hai gou shen, believed in traditional Chinese medicine to improve virility. Seal penises are the animal’s most valuable part, selling for approximately $2,000 a pound on average, according to Yavuz.

‘Three-Step’ Killing Process

The customary way to kill pups is to knock them unconscious with a heavy wooden club, then pierce their main heart vessels with a pick or knife to kill them. But the Cape fur seal is a difficult target. “Its agility on land means that when you’re taking a swing at it, it takes evasive actions,” Pat Dickens says. “Clubbing nursing pups in large social colonies is unlikely to be swift and accurate and is extremely stressful.”

Adult seals are shot in the head. “I have 126 rifles on site,” Yavuz says. “Their accuracy is over 86 percent. They’re Boers and Angola war veterans, so great shooters.”

In 2010, on the basis of footage of Namibian seal hunts made by filmmaker Bart Smithers, David Lavigne, then of the International Fund for Animal Welfare, and Stephen Kirkman, who’s associated with the University of Cape Town and works for South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs, asserted that the hunts fail to follow the “three-step” killing process.

Those steps—recommended by the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare of the European Food Safety Authority and by a group of independent veterinarians—are: stun, monitor, and bleed. Stunning involves destroying the seal’s brain sensory function through a club blow or rifle shot. Monitoring means ascertaining if the seal is still conscious by checking its blink reflex and, if it is, immediately administering another stunning blow. Only then are the seal’s heart blood vessels pierced to guarantee “humane slaughter.”

According to Dickens, some sealers are migrant workers who are paid a meager wage and live in makeshift shacks. It’s unlikely, he says, that they’ll have had adequate training in humane killing methods, such as verifying that a seal has been successfully stunned before swiftly piercing its heart vessels.

CITES stipulates that wildlife exports be prohibited if they violate a country’s laws. According to Namibia’s 1962 Animal Protection Act, beating or terrifying an animal or causing it suffering is an offense. But the wording of the act has been the subject of controversy between anti-hunt campaigners and Namibian officials.

Among those officials is John Walters, Namibia’s “ombudsman,” charged with defending human rights, including in the context of environmental protection. In 2012 Walters looked into complaints against the seal hunts by civil society organizations, NGOs, and individuals. He acknowledged that Cape fur seals are moving targets that flee hunters at speeds that make accurate hits difficult.

But, Walters rationalized, the Animal Protection Act applies only to domesticated animals and wild animals that are either captive or “under the control of any person.” By Walters’s logic, because seals being chased by sealers are moving away from them, the animals aren’t under the sealers’ control and therefore aren’t protected by the act.

An outcry from organizations like Sea Shepherd, an NGO devoted to marine wildlife conservation, ensued, but Walters stuck to his position, concluding that clubbing remains the most practical way to kill the pups while a rifle shot to the head is the ideal way of killing adult bulls.

When asked if his interpretation of the law has changed since 2012, Walters responded, “I cannot add anything further than what I have considered and found in my report.”

Yavuz invoked Walters’ reasoning almost verbatim as to why the act doesn’t apply to seals. On the question of how seals are killed, he says he’s tried unsuccessfully to use sound bombs—nonlethal explosives that deafen and stun—to make it easier to target individual pups. But, he says, “clubbing and shooting remain the best methods of killing.”

Seals by the Numbers

As early as the 1600s Dutch settlers killed Cape fur seals for their skins and oil. By the 20th century, seals had been extirpated from most of their breeding colonies and were limited to small, relatively inaccessible islands. That’s when harvests became legally controlled, and designated sealing seasons were set. As a result the seals recovered—although they’ve been displaced almost entirely to the mainland by human activities on islands, such as guano collecting.

It isn’t clear how stable Namibia’s seal populations are today. The hunting season runs 139 days, from July through November, giving the animals little respite. Sealers target larger pups and allow the smaller, thinner ones—those with poorer chances of survival—to get away. This can weaken the long-term genetic vigor of the populations.

A South African biologist who has studied Cape fur seals for several decades—and asked not to be named because of the controversies surrounding Namibia’s sealing—believes that the hunt quota of nearly 90,000 “is way too high for a sustainable industry. The quota is set on the basis of the size of the entire population, but only two colonies are harvested. The high quotas for pups mean that very few, if any, can survive in typical years at these two colonies.”

The hunts are essentially invisible. “No trespassing” signs are posted at the colonies—Cape Cross and Wolf/Atlas Bay—and violators have been arrested. The latter colony also happens to be on a mining concession leased by De Beers, the world’s leading diamond company, which is strictly off-limits. When asked about De Beers’s position on Namibia’s covert seal hunt, Patti Wickens, the company’s environmental principal, said, “There has been no seal culling in any of our mining license areas in the last two years, and we remain hopeful that this will continue into the future.”

But it’s only a matter of time before sealing resumes there. Both Yavuz and Dickens confirmed that there are still two recognized sealing concession areas. While the previous concessionaire at Wolf/Atlas Bay had shut down his operation, new concessionaires are busy building a seal-processing plant at Lüderitz and may resume sealing before the end of this harvest season.

Do Seals Undermine Namibia’s Fishery?

Namibia’s fishermen perceive seals as competing for such commercially valuable species as mackerel, sardines, anchovies, hake, and herring. Seals are known to snatch fish right off fishing lines, and fishermen say that seals sometimes damage their gear, doing things such as tearing trawl nets in order to remove fish from them. But Kirkman says seals typically just take the “stickers—fish sticking through the net.”

The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources encourages sealers to take the full allowable yearly catch of nearly 90,000. The ministry itself sets that allowable catch—a seeming conflict of interest, exacerbated by the fact that hunts are also supervised by inspectors from the ministry without external oversight. Representatives with the head office of the ministry did not respond to questions about this and other matters relating to sealing and fisheries.

Does the killing of tens of thousands of seals each year ameliorate fishermen’s perceptions that seals undermine their livelihoods? Hatem Yavuz doesn’t think so. “If [the quota] were higher, such as an annual of 500,000 seals,” he says, “then our business might improve how fishers view seals.”

Two decades ago, before Patti Wickens became De Beers’s environmental spokesperson, she conducted studies that led her to conclude that seals had negligible effects on the fishing industry. Wickens declined to comment on the effects seals have on fisheries today.

“If you took all of Namibia’s seal colonies and created a super colony, it would stretch a mere 11 miles of coastline,” says Seals of Nam’s Dickens. “How can seals destroy your fishing industry when your coastline is over 900 miles long?”

According to Stephen Kirkman, the fishing industry may hurt seals more than the other way round. He is one of the authors of a forthcoming update of the conservation status of the Cape fur seal that describes threats to seals: drowning in fishing nets, illegal killing by fishermen, deadly entanglements in marine debris.

‘Golden Retriever Puppies in Wetsuits’

Despite the worldwide trend against sealing, Namibia’s industry is far from shrinking. The new Lüderitz seal-processing plant is described as an “empowerment project” to generate jobs, support young entrepreneurs, and contribute to the local economy. The plant is expected to have the capacity to process 40,000 seals a year, including their skins, oil, and meat. Meanwhile an environmental impact assessment of the plant reported that little information has yet been provided about the chemicals that will be used in the plant, especially in the tannery, exposing potential risks to people and the environment.

Seal king Hatem Yavuz is forging ahead with sales of seal products to Russia and China. Meanwhile, Canadian seal traders say that encouraging Chinese demand is key, as is diversifying the trade. For example, Bernie Halloran, the CEO of PhocaLux International, is advertising seal bones for grinding up into a “health-giving” powder, and banking on Korea and Japan to purchase seal meat.

But Rebecca Aldworth, executive director of Humane Society International/Canada, says that China “has never materialized as a significant market for any seal product.” Nevertheless, Chinese companies recently tried to intercept the Nambian Sunshine business by attempting to seize sole rights to the country’s seal oil. And according to a September 13 article in the Namib Times, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources is now contemplating granting a Chinese businessman’s request to import live seals—and possibly cetaceans too—for the Asian aquarium trade.

If Namibia were to shut down its sealing industry, say Economists at Large, a team of environmental economists concerned with sustainability, an economically viable alternative exists: seal-watching tourism, which could generate 300 percent more revenue—and jobs—than seal hunting.

“Seals may not be as popular as whales, dolphins, or sharks, but seeing a colony is guaranteed,” Stephen Kirkman says. “You can be sure that a whale or dolphin-watching operator will include a spin to the seal colony in their tour, as they then never have a situation where their customers come away with having seen nothing. Most people are quite satisfied after seeing a seal colony.”

Monica Taylor runs a company called Offshore Adventures, out of Plettenberg Bay, South Africa, that offers swimming with seals. Since January 2011, when the company got started, some 10,000 people have swum with seals. For three consecutive years Offshore Adventures has won the prestigious Wessa blue flag, an international award for environmental excellence.

“There’s no better way of conducting environmental education and awareness than through experiences like these,” Taylor says. “Swimming with seals is the best combination of adventure, animal encounters, and sustainable tourism. Due to their inquisitive nature, we don’t have to chase after them or feed them to interact. They’re golden retriever puppies in wetsuits.”

While seal-based tourism could be a win for Namibia and the seals, a leading question remains: Which of the vested interests will prevail?

This article was first published by National Geographic on 21 Sep 2016.

We invite you to share your opinion whether Namibia’s cape fur seal trade be banned? Please vote and leave your comments at the bottom of this page:

Thank you for voting.

Leave a Reply