Every year I get several letters like one that came in mid-February from WXPR listener Doug Heise, who lives in Rhinelander and has been feeding birds for 30 years. He wrote about the species he’s fed over the years: “So many different varieties. chickadees, nuthatches, many types of finches, Pine Siskins, Chipping Sparrows, cardinals, Blue Jays grosbeaks, and many more. Also way too many squirrels.” Doug continued:

What a difference a year makes. Right now I am lucky to see anything. Maybe an occasional chickadee or American Goldfinch. My feeders are always clean and my feed is always fresh. I live in a rural area and had no habitat changes. I have not seen a squirrel since Christmas. I have talked to many people from outdoor magazines and my local DNR. No one seems to care. I miss my birds. Can you tell me anything? Is there a group that you can lead me to that can help? After 30 years of feeding birds I think am going to quit. Change my mind.

It’s not my place to change anyone’s mind about feeding birds. We set out feeding stations for two reasons—to help the birds and for our own enjoyment. I can’t judge anyone else’s pleasure levels, so I never counsel anyone to feed or not feed on that basis. If feeding birds becomes more frustrating and distressing than pleasurable, it may be time to stop, but that is not for me to say.

What I do counsel on is how to ensure that our bird-feeding practices are genuinely helpful for birds without harming them. We know, based on several studies in Wisconsin as well as other places, that bird feeding does help winter survival of Black-capped Chickadees and almost certainly some other species. We also know that some elements of feeding can be harmful, directly or indirectly, and we need to factor those into our decision about whether our feeding practices are harmful or not.

Doug specifically mentioned using fresh seed, which is extremely important for the health of birds, especially during winter thaws and as snows melt in spring, when bacteria and fungus can thrive on shells and uneaten seeds. Some finches shun even new nyjer seed if it was overheated by the supplier and is too dry, but that wouldn’t affect the numbers of other species, much less squirrels. That’s not Doug’s problem.

A few kinds of bird feeders, especially mesh bags, may, very rarely, entangle a bird. Last week I heard of one case of a chickadee who got caught in the suet cage part of a feeder. We’re hoping it survived. But those freak accidents never lead to the loss of all the birds in a yard, much less the squirrels.

Many registered lawn and garden pesticides present a serious danger to backyard birds—it seems very wrong to set out feeders or other bird attractants in any yard treated by lawn-care services, which refuse to divulge which pesticides they use as trade secrets. It’s also wrong to use any pesticide products without researching their potential effects on wildlife and the best ways to use them to minimize danger. But although issues with regard to pesticide use contribute to long-term population declines, they wouldn’t be related to a sudden winter disappearance like Doug is seeing.

When natural predators, such as nesting Merlins or Cooper’s Hawks, or domestic ones such as outdoor cats, are lurking nearby, it’s a good idea to close down your feeders for the duration. Raptors don’t nest in winter, and those wintering in the vicinity of a feeding station, as well as Northern Shrikes, aren’t likely to stick around week after week. Cats are more insidious than natural predators because they are subsidized killers—people feed them and provide shelter and veterinary services, and so their numbers don’t drop as prey populations decline, nor are they ever forced to move on when they’ve depleted the birds in an area, as happens with natural predators. Cats are estimated to be the number one direct cause of bird mortality in the United States, killing more than a billion wild birds in this country every year and, especially on islands and shorelines, taking threatened and endangered species in disproportionate numbers. But again, I presume Doug would have told me if he was having an issue with wild predators or cats.

The windows on our houses present another clear and present danger. Bird feeders set anywhere from about 3 feet to 30 feet from windows are associated with disproportionate numbers of bird deaths from window collisions. Many studies have found that feeders set directly on the glass or within a foot or two of the glass are much less likely to be implicated in bird deaths than those further away, unless they’re so far from the house that you need binoculars to see the birds. In my own yard, I’ve found that when I have a feeder or two affixed to the glass with suction cups or directly below the glass attached to the window frame, collisions at that window drop to zero. Many people don’t make the connection between their bird-feeding practices and birds crashing into their windows, but regardless, even worst-case scenario window mortality at one house or in one neighborhood wouldn’t cause the sudden disappearance of both birds and squirrels that Doug is seeing.

So why are there fewer birds, and squirrels, at Doug’s feeders this year? First let’s look at the best way we have for accurately measuring bird declines and why it isn’t enough to explain disappearances in one backyard.

In 1966, my personal hero, Chandler Robbins, created our best measure for bird population health. The Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) tallies the number of birds seen or heard during the breeding season on thousands of routes censused by thousands of qualified birders and biologists. The vast majority of birds counted are singing males defending their territories. Any “floaters” waiting in the wings for an opening to take over a good quality territory if the territory holder dies bide their time quietly, so they aren’t detectable on the BBS. When all suitable habitat is filled with territory holders, there’s no way of knowing how many non-singing floaters are out there. Those birds are what we used to call a “surplus population.” And the Breeding Bird Survey is not designed to measure that. It’s possible for a species to appear perfectly healthy and stable using Breeding Bird Survey numbers until we’ve lost a critical mass—that surplus population—at which point the population can show a rapid drop even if the loss of individuals per year is no larger than it was when it seemed more robust. Not even our very best system of counting birds is perfect.

A researcher specializing in assessing migrating bird numbers from NEXRAD radar, Sidney Gauthreaux, found huge declines in the mass of migrating birds flying over the Gulf of Mexico—50% between the 1960s and the 1980s, and another 50% from the 80s to the turn of the century—while Breeding Bird Surveys of various Neotropical migrants were not showing a corresponding decline. Many older birders like me have noticed fewer “good days” and generally smaller flocks of migrating birds during spring and fall than we used to. We still have exceptionally good days of spring and fall birding, of course, but not of the magnitude or frequency we remember.

But not all species are declining, and even when the Breeding Bird Survey shows a sudden decline on a route or within a region, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the actual numbers of birds of that species have dropped—it can also mean that important habitat has been lost so those birds moved elsewhere. Of course, if there is no suitable habitat elsewhere, those individuals will eventually die out, so any decline in BBS numbers indicates a potential serious problem, and when the overall BBS numbers for a species over the continent drop, there is most certainly a serious problem.

When BBS numbers increase for a species, that can mean that suddenly there is more habitat than normal so more floaters suddenly can find and defend a territory. In the first years when a fire or logging opens up second growth, local BBS routes will show a decline or disappearance of those species that needed the old growth and an increase in species that prefer more open habitat. Those increasing birds didn’t magically appear—they were floaters that discovered the newly appropriate habitat during migration or other normal wandering. From one year to the next Breeding Bird Survey numbers for just about every species fluctuate, often quite dramatically, and the only way we have a sense of the overall trend is to look at those numbers over a wide number of routes over decades. Unfortunately, with the sequester and reduced funding of many federal agencies, we don’t have updated information from the last few years on the Breeding Bird Survey website, but we can see the data to look at longterm trends from 1966 through 2012.

Black-capped Chickadee numbers have been consistently steady or rising during that period over most of their range, with the rise both steady and significant in Wisconsin.

Both Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers have been holding steady, but not significantly increasing.

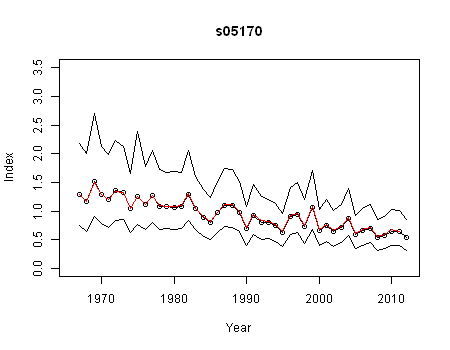

Some species are irruptive, with wide fluctuations from one year to the next. It can be tricky to tease out whether they are increasing or declining from one year to the next, but overall patterns can be seen with decades of data. For example, Pine Siskin numbers appear to be declining over the continent.

The boreal forest areas of Minnesota have historically been within the breeding range of Pine Siskins. As an irruptive species, numbers fluctuated from year to year, but the peak numbers historically have been much higher than they’ve been in the past decade.

Wisconsin doesn’t have as much boreal forest as Minnesota, so has never enjoyed the major breeding bird number peaks that Minnesota has. What population peaks have been seen in Wisconsin are smaller in the past decade than earlier peaks. If you look at the scale of the graphs, the peak numbers ever counted in Wisconsin were less than a third of the peak numbers in Minnesota.

If Pine Siskins are not declining but simply shifting north of where we census them, we shouldn’t be seeing declines in winter numbers. Unfortunately, Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count data is collected earlier in the season than many Pine Siskins wander south, and the Great Backyard Bird Count hasn’t been done long enough to be able to see long-term trends yet. The number of Pine Siskins seen on Minnesota and Wisconsin Christmas Bird Counts from 1900 through 2015 has fluctuated from one year to the next without any really clear trends. So overall, this data isn’t all that helpful:

Numbers of breeding Purple Finches are declining noticeably on a continent-wide scale and in Minnesota, but not in Wisconsin:

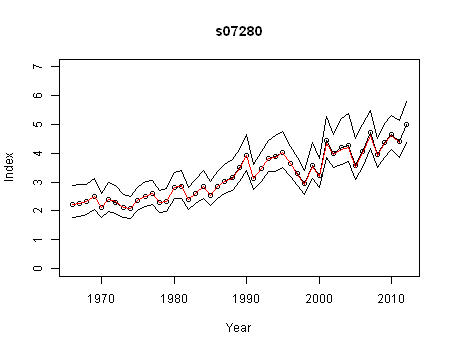

Red-breasted Nuthatches are irruptive, and their numbers swing crazily from year to year, but show a clear increase.

White-breasted Nuthatches are not irruptive, but also show an increase:

So where are the birds at Doug Heise’s Rhinelander feeding station? And where are his squirrels? It sounds trite and even ridiculous to say “no one really knows,” and that is certainly not an answer that Doug Heise wants to hear. Unfortunately, it’s the truth.A secretive Great Horned Owl might have taken or scared off most of the squirrels, but smaller songbirds don’t typically flee from large owls—little birds may mob one, but aren’t all that threatened by large owls. And it’s not likely that his yard would be plagued by both a predator focused on squirrels and one that took mostly small feeder birds suddenly at the same time.

This year, I’ve had lots of American Goldfinches and quite a few Pine Siskins in my own yard. Someone in my own neighborhood closer to the Lester River has siskins and redpolls, but not goldfinches. Two weeks ago at the Sax-Zim Bog north of Duluth, I saw lots of Pine Siskins and a few redpolls, but no goldfinches. So these numbers can fluctuate unexpectedly within small areas.

What seem like minor changes in my own neighborhood habitat have occasionally led to fairly big if temporary changes in bird numbers. One or two fallen trees can lead to an increase in Pileated Woodpeckers here, and since this happens very quickly, it can’t be due to a sudden increase in reproduction—it’s almost certainly because Pileated Woodpeckers that had been hanging out in another neighborhood discover better pickins right here. And Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers sometimes follow Pileateds. So someone in another neighborhood might note a sudden decline in woodpeckers right when I’m noticing a sudden increase, even as the overall population remains steady.

When my neighbor started offering mealworms to the birds in her yard, some of my birds switched from my yard to hers. It’s possible that someone not far from Doug’s place started up a feeding station and the birds and squirrels decided to switch eating establishments for a while.

Noise pollution can sometimes send birds packin’—if anyone is operating a chain saw or producing some other loud sound more regularly than local wildlife can handle, that could send them on their way.

Of course, it’s also possible that there are just as many birds as ever right there, but due to happenstance, this year there is so much natural food available that none of them are visiting feeders.

It would be interesting to hear from other readers in the Rhinelander area to find out if they, too, saw lower-than-normal numbers of birds and/or squirrels this winter. It’s unlikely that we can pinpoint an exact cause, but would be valuable to know how widespread the problem is. Let me know how your bird numbers are by emailing me at [email protected].

Laura Erickson

Laura Erickson, 2014 recipient of the American Birding Association’s prestigious Roger Tory Peterson Award, has been a scientist, teacher, writer, wildlife rehabilitator, professional blogger, public speaker, photographer, American Robin and Whooping Crane Expert for the popular Journey North educational website, and Science Editor at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. She’s written eight books about birds, including the best-selling Into the Nest: Intimate Views of the Courting, Parenting, and Family Lives of Familiar Birds (co-authored by photographer Marie Read); the National Outdoor Book Award winning Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids; 101 Ways to Help Birds; The Bird Watching Answer Book for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology; and the National Geographic Pocket Guide to Birds of North America. She’s currently a columnist and contributing editor for BirdWatching magazine, and is writing a field guide to the birds of Minnesota for the American Birding Association. Since 1986 she has been producing the long-running “For the Birds” radio program for many public radio stations; the program is podcast on iTunes. She lives in Duluth, Minnesota, with her husband, mother-in-law, licensed education Eastern Screech-Owl Archimedes, two indoor cats, and her little birding dog Pip.

Leave a Reply