It’s been one delay after another in the case against South African alleged rhino poaching kingpin Dumisani Gwala and his two co-accused. The reported reasons run the gamut—changes in venue, changes in magistrates, changes in defense counsel, and requests by Gwala’s defense attorney for more time because of a lack of preparation.

The trio was arrested in December 2014 in KwaZulu-Natal, in northeastern South Africa, as part of a months-long undercover operation where officers posed as rhino horn sellers and now face a combined 10 charges relating to the illegal purchase and possession of rhino horn and resisting arrest, according to South Africa’s Times Live. Gwala is now out on bail.

At the time of his arrest, officers told South Africa’s IOL News they believed that roughly 80 percent of illicit horns in KwaZulu-Natal likely passed through Gwala’s hands—and that he allegedly led the biggest rhino-poaching syndicate in the province, where he acted as a middleman between buyers and poachers and also organized and outfitted poachers locally and in Mozambique.

Last year 162 of the 1,054 rhinos poached in South Africa were killed in the province, and the numbers keep going up.

On October 9, after being postponed at least 16 times, according to South Africa’s Sunday Times, the case again came before the Ngwelezane Magistrate’s Court, in the town of Empangeni in KwaZulu-Natal.

It was more than a year since I’d sat in that same courtroom for a hearing, and the case was no closer to completion. And yet this time, with the sudden removal of the prosecutor, Yuri Gangai, it was again put off, making it look, on the surface at least, as if justice may have taken a step backward.

PLANNED REQUEST FOR MAGISTRATE’S RECUSAL

Gangai told National Geographic that he had been on the verge of making an application for the recusal of the magistrate, Kwazi Shandu, owing to allegations of corruption that had appeared in the press.

In July the Sunday Times reported on an affidavit that had come to light claiming that “bribes have been paid to ensure that the case is dragged out” and noting that this was “part of a broader investigation into alleged corruption within Zululand courts.”

According to Prosecutor Gangai, he intended to ask for the magistrate’s recusal at the October 9 hearing because those allegations created an appearance of bias. “My application for recusal was to ensure a neutral forum,” he said.

He noted that his planned request did not imply that the magistrate was guilty of those allegations but rather that it was “important for a fair trial that you don’t have an appearance of favor of one side.”

Three people—two police officers and an environmental activist—told National Geographic that Gangai had asked them the previous week to testify and that they had prepared sworn statements supporting the application.

One, a senior police commander investigating the affidavit mentioned by the Sunday Times, said he planned to say that he supported a full investigation of the claim that a payment had been made to take it easy on Gwala—especially because many other claims in that same affidavit had checked out. He was also going to encourage that the trial be moved or heard before an independent magistrate to avoid any possible bias.

Gangai, however, never made any request or called any witnesses, because late on the Friday before the hearing on Monday, October 9, he was taken off the case, and three new prosecutors were assigned.

According to the Sunday Times, KwaZulu-Natal’s director of public prosecutions, Moipone Noko, denied allegations that her decision to pull Gangai was “akin to sabotage” and that the recusal application wasn’t lodged by the new prosecutors “because the case, as it stood then, had neither evidence nor valid grounds to base a recusal of the magistrate application on.”

Both Shandu and Gwala’s defense attorney, Mpumelelo Linda, declined to comment for this article.

REASONS FOR PROSCUTOR’S REMOVAL

When asked why Gangai was removed from Gwala’s case, Noko said that new prosecutors were assigned for “fair allocation of cases” and logistical reasons. According to Noko, “It is not cost effective to have a prosecutor traveling from Durban to the north coast to deal with a case that can be dealt with by senior and experienced prosecutors” in that part of KwaZulu-Natal.

Yolanda Gielink, a criminal defense attorney in Empangeni, has followed the case closely. She has defended hundreds of clients accused of crimes such as murder, rape, theft, and park guards accused of crimes by rhino poachers.

She pointed out that removal of a prosecutor is unusual. When a conflict of interest arises, she said, the prosecutor will recuse herself and request a replacement. Or some prosecutors may decide they’re not equipped to deal with a case, perhaps because of a lack of relevant experience, and will ask for a replacement. But, she said, “Advocate Gangai is very experienced, and there was no conflict of interest.”

Further, Gielink noted, saving money as the rationale for a prosecutor’s removal “has not been an issue for as long as I can remember. There are many state advocates that travel all over our province. Cutting costs is cutting on justice.”

Since his removal Gangai has prosecuted other cases in that same Ngwelezane court. This suggests that the need to cut travel costs—the trip from Durban, where Gangai lives, is only a hundred miles—wasn’t the real justification for his removal.

NORMAL LEGAL WRANGLING?

While the motivations behind these legal maneuvers remain unclear, they raise questions about their possible impact on rhino poaching in KwaZulu-Natal.

“[These delays] send out a strong message that crime pays,” says Megan Carr, of the South Africa-based conservation organization Rhinos in Africa Foundation.

According to IOL News, in January 2017 two brothers linked to a network called the “Boere rhino mafia,” Deon and Nicolaas van Deventer, were arrested again with a rhino horn after pleading guilty 10 years earlier to poaching rhinos. As reported by South Africa’s News 24, in 2007 they were caught poaching rhinos in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park while out on bail for another arrest, the previous year, for allegedly poaching at least 22 rhinos.

This year is already KwaZulu-Natal’s bloodiest, with 193 rhinos slaughtered through the end of September, according to Musa Mntambo, spokesperson for Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, the province’s wildlife conservation authority. At that rate poaching in KwaZulu-Natal is on track to be more than 50 percent higher this year than in 2016, when 162 rhinos were killed in the province.

Altogether South Africa has about 70 percent of the world’s rhinos, but during each of the past five years more than a thousand were killed, and 529 were killed nationwide during the first six months of 2017. The killings in Kruger National Park, long the epicenter of the slaughter, have dropped thanks to concentrated anti-poaching efforts, but elsewhere, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal, they’ve increased.

According to a May 2017 report by WildAid, an NGO dedicated to stopping the illegal wildlife trade, corruption, procedural incompetence, and a failure to prosecute mid- and higher-level trade operators have fueled the rhino crisis in South Africa.

“This is sadly typical of what’s been going on in South Africa for years,” says Susie Watts, the report’s author. “The country will never get control over rhino horn trafficking until it gets control over the judiciary. Time and again we’ve seen rhino criminals getting away with their crimes, leaving them free to re-offend and providing absolutely no deterrent to others.”

According to South Africa’s Herald Live, three men who formed the so-called “Ndlovu gang”—Forget Ndlovu, Jabulani Ndlovu, and Sikhumbuzo Ndlovu (all unrelated) who were suspects in almost a hundred rhino killings, including 50 in KwaZulu-Natal—were rearrested on new poaching charges just two weeks after being released on bail for an earlier arrest. In June 2016 they were arrested in possession of a darting rifle and newly removed rhino horn. Dispatch Live reports that they face charges related to the killing of 22 rhinos in 13 incidents, and their trial is scheduled to start on November 30.

“Not enough is being done,” says Grant Fowlds, project coordinator of community conservation for Project Rhino, a KwaZulu-Natal association that includes the provincial government conservation agency, private and community-owned reserves, rhino owners, leading conservation NGOs, and anti-poaching security specialists.

“When poachers and traffickers start getting 25 years in jail, they will start thinking about the risks,” Fowlds says. “But the opposite is happening.” Poachers will avoid places where there is tough enforcement, tough prosecutions, and tough sentences, he says. “To a certain extent it has happened at Kruger.”

In Kruger, even though the number of incursions has increased—from an average of 6.7 a day in 2015 to 7.9 in 2016—rhino killings in that period fell by 20 percent, from 826 to 662.

According to Fowlds, KwaZulu-Natal, by contrast, “has become the next killing field.”

Many people call it “’the catch-and-release’ province,” because shortly after rangers catch suspects, the justice system releases them, says Bonné de Bod, a South African investigative journalist and filmmaker. For the past three years she’s been documenting the rhino poaching crisis for her feature documentary, STROOP, to be released in mid-2018.

“With nothing stopping these poaching gangs, there has been a dramatic increase in poaching numbers,” de Bod says. “These alleged poachers need money, and a lot of it, to hire good defense teams. So they go right back into these provincial reserves to poach more rhinos. It’s just so frustrating because the rhinos don’t have time on their side.”

Dumisani Gwala’s trial is scheduled for May 2018.

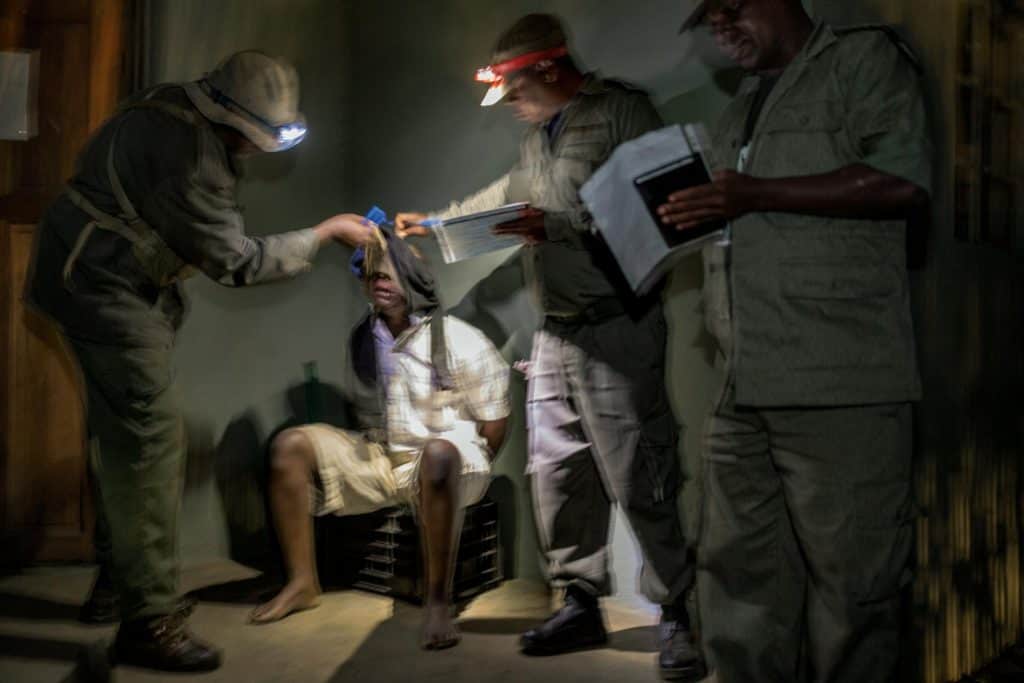

This article was first published by National Geographic on 13 Nov 2017. Lead Image: Poaching is on the rise in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, where this white rhino was dehorned with a chainsaw by poachers. Photograph by Brent Stirton, Getty/National Geographic Creative.

We invite you to share your opinion whether South Africa should strictly enforce its anti-poaching legislation? Please vote and leave your comments at the bottom of this page.

Thank you for voting.

What you can do

Support ‘Fighting for Wildlife’ by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute. Thank you.

Leave a Reply